What’s Happening to Kazakhstan’s Oil Exports After the Novorossiysk Drone Strike?

Photo: CPC

Photo: CPC

The Ukrainian strike on Novorossiysk’s port using naval drones happened on November 29, but its consequences for Kazakhstan’s oil exports are still unfolding. Orda.kz examined what has happened since.

Although this wasn’t the first time infrastructure tied to the Caspian Pipeline Consortium (CPC) had come under attack, it was by far the most damaging. The strike heavily crippled one of the single-point moorings, SPM-2, and repairs are expected to take months.

SPMs are the offshore terminals through which CPC pumps oil to tankers. The system in Novorossiysk has three— SPM-1, SPM-2, and SPM-3 — but SPM-3 has been offline for scheduled maintenance since mid-November. As a result, CPC now operates with only one functioning berth. This is a major choke point, given that the pipeline carries around 80% of Kazakhstan’s total oil exports and roughly 1% of global supply.

Reuters reported that SPM-3 is tentatively expected to resume work on December 11–13, although bad weather has slowed underwater repairs.

CPC, after meeting with KazMunayGas leadership, said only:

The head of the consortium informed the head of KMG that the CPC team and contractors are currently at the marine terminal replacing the hoses on the CPC-3 single point mooring unit.

Diplomatic friction followed quickly. The Kazakh MFA issued a formal protest:

"We expect the Ukrainian side to take effective measures to prevent similar incidents in the future."

Ukraine’s response was unequivocal:

No actions by the Ukrainian side are directed against the Republic of Kazakhstan or other third parties— all of Ukraine's efforts are focused on repelling full-scale Russian aggression within the framework of the exercise of the right to self-defense guaranteed by Article 51 of the UN Charter.

Kazakhstan later confirmed ongoing discussions with Kyiv.

MFA spokesman Aibek Smadiyarov said:

We will not comment further on this issue. We are maintaining contact with the Ukrainian side and will continue to work through closed diplomatic channels.

Meanwhile, analysts stress that CPC is overwhelmingly a Kazakh export route. Sergey Vakulenko of Carnegie Berlin notes that only about 15% of the crude in the system is Russian.

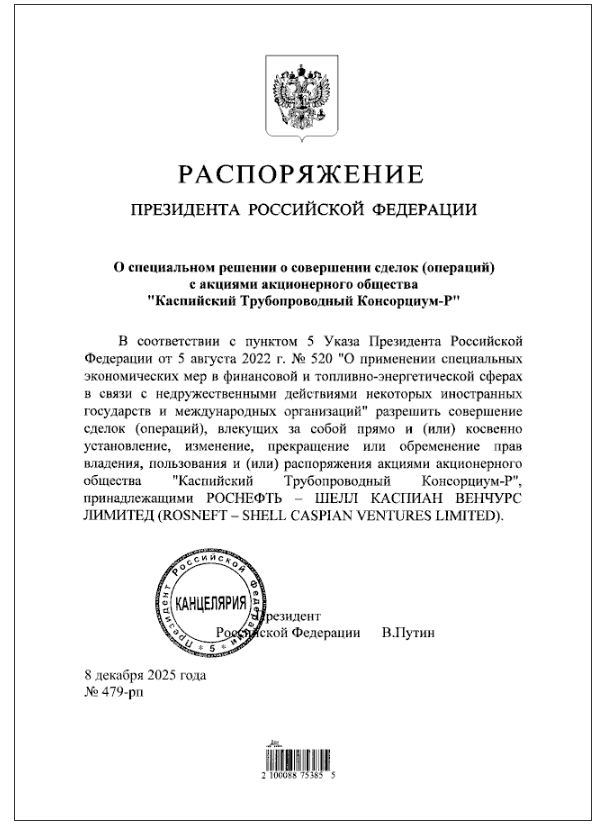

CPC regularly publishes its shareholder structure:

CPC shareholders: Russian Federation — 24% (represented by Transneft — author’s note), MC CPC Company (LLC) — 7%, JSC NC KazMunayGas — 19%, Kazakhstan Pipeline Ventures LLC — 1.75%, Chevron Caspian Pipeline Consortium Company — 15%, Lukoil International GmbH — 12.5%, Mobil Caspian Pipeline Company — 7.5%, Rosneft-Shell Caspian Ventures Limited — 7.5%, BG Overseas Holdings Limited — 2%, Eni International NANSar.l. — 2% and Oryx Caspian Pipeline LLC — 1.75%.

The impact on exports has been immediate.

Reuters estimated last week:

"An industry source estimated the loss of CPC capacity with only one SPM at 900,000 tonnes per week."

Experts also report a significant drop in Kazakhstan’s oil production — 1.9 million barrels per day lost — due to limited transport capacity.

Kazakhstan has scrambled to divert at least part of the volumes. On December 9, it became known that Kashagan oil would, for the first time, be rerouted to China via the Atasu–Alashankou pipeline. CNPC plans to take 30,000 tons in December, and Inpex about 20,000.

Yet compared to CPC’s theoretical December capacity of roughly 2.7 million tons with one functioning SPM, these diversions remain symbolic.

There were also media reports of plans to boost shipments through Azerbaijan via the Baku–Ceyhan corridor. But Vakulenko emphasizes the limits:

The main problem is that oil can be delivered from Kazakhstan to Baku either through Russia, which Moscow is unlikely to agree to, or by tankers. But there are currently only about 20 tankers in the Caspian Sea with a capacity of eight thousand tons or less. And Kazakhstan's main oil port, Kuryk, can only ship 200,000 barrels per day. Theoretically, Kazakhstan could build an offshore pipeline to Azerbaijan. Moreover, with the adoption of the Convention on the Legal Status of the Caspian Sea in 2018, this no longer requires the consent of all littoral states. However, numerous technical challenges remain, due to the lack of appropriate heavy equipment in the sea-lake. And in any case, such a project would be impossible to implement in three years.

Meanwhile, Russia may be preparing changes to its own presence in the consortium. On December 8, President Vladimir Putin authorized Rosneft-Shell Caspian Ventures Limited to conduct transactions involving its 7.5% stake.

Some experts, however, argue the opposite may be in play.

Oil analyst Nurlan Zhumagulov said:

Many believe Shell is buying out Rosneft's stake. But the logical course would be for Rosneft to buy out Shell's stake. Then, it would acquire 12.5% from Lukoil. Russia would then control 51% of the CPC.

But he added that such moves would collide directly with U.S. sanctions, as the US Treasury Department has prohibited the alienation of shares in KTK.

For now, Kazakhstan remains reliant on a pipeline corridor that is both indispensable and vulnerable — while alternatives remain either too small, too slow, or too politically complicated to replace it anytime soon.

Original Author: Igor Ulitin

Latest news

- The War in Iran Opens a Window of Opportunity for Kazakhstan’s Oil Sector, Analysts Say

- Iran Conflict Escalates Beyond the Gulf: What Kazakh Experts Say About Risks for Central Asia and Kazakhstan

- Kazakhstan Prepares Possible Evacuation of Its Citizens From Iran

- LRT in Astana Is Reaching the Finish Line: The Launch Is Expected in the Coming Months

- Kazakhstan Ready to Help the UAE Amid Escalation in the Region

- Tokayev Discusses Middle East Escalation With Qatar’s Emir

- Airlines Ready to Bring Kazakhstanis Home From the Middle East

- Tokayev Sends Support Messages to Gulf Leaders Amid Regional Escalation

- Kazakhstan Bans Its Airlines From Flying Over Several Middle East Countries

- Astana Strengthens Security Measures Amid Escalation Around Iran

- Tokayev Meets U.S. Ambassador Stufft, Discusses Board of Peace Cooperation

- Mangystau Launches AI-Assisted School Monitoring to Prevent Teen Suicidal Behavior

- Kazakhstan to Supply UK With Critical Minerals

- AI Faculties for Educators to Open in Kazakhstan: What Other Changes Are Coming to the Education Sector

- There Are Medals — But Not Enough Ice: What’s Happening to Figure Skating in Kazakhstan

- Is Kazakhstan’s Nuclear Power Plant Project at Risk After New UK Sanctions? Rosatom Responds

- Prosecutor General’s Office Suspends Extradition of Navalny Ex-Staffer Detained in Almaty

- Former EBRD Executive Jürgen Rigterink Elected as New Independent Director on Bank RBK’s Board of Directors

- Kazakhstan Near Bottom of Retirement Comfort Ranking

- Kazakhstan to Open New International Flights Across Asia, the Middle East and Europe