Inside Qazaqfilm: Orda.kz Explores the State of the National Film Studio

Photo: Orda.kz / Igor Ulitin

Photo: Orda.kz / Igor Ulitin

Orda.kz journalists visited the national film studio to see what it’s like on an ordinary day.

In recent years, Qazaqfilm has become inseparable from controversy, to the extent that its everyday life is often overshadowed. What’s really happening at the legendary film studio? To find out, Orda.kz reporters toured the grounds, guided by staff members.

First Impressions: A Tired Grandeur

Just beyond the entrance gate, visitors are welcomed by a bust of Shaken Aimanov and Qazaqfilm’s own “walk of fame,” honoring prominent actors and directors. It can be seen by anyone walking past the film studio along Al-Farabi Avenue.

Beyond the alley, the iconic two-pavilion building rises, impressive, but weathered. Water stains streak from the roof, and signs of wear are evident both inside and out. It’s clear the facility hasn’t seen major renovations in many years.

Inside, the corridors feel more cavernous than welcoming, and within the pavilions themselves, the outdated infrastructure is evident. Rusting ventilation boxes, aged electrical panels—much of it untouched since Soviet times, employees confirmed.

Lighting adjustments are still done in the old-fashioned way. We watched as a technician extended a pole several meters high to adjust overhead fixtures. As it turns out, this method is still standard in many film studios. And when asked if things were done the same way in Hollywood, the response came with a smirk:

Well, you’re really comparing apples and oranges!

Qazaqfilm still holds strong appeal for filmmakers.

According to the staff, it remains the most practical place in Kazakhstan for indoor shoots. The reasons are simple: first, logistics—trucks carrying equipment, props, and set pieces can drive directly into the space.

Second, the soundproofing is excellent; it blocks out everything from nearby traffic to rain. And third, it’s affordable — pavilion rental runs around 250,000 tenge per day, which they say is a very fair rate.

Had we visited just two weeks earlier, we would’ve seen the set of the TV series Golden Horde — complete with sand-covered floors and yurts.

Instead, we caught the tail end of set construction for an upcoming TV show on one of the local channels.

Cosmetic repairs are slowly underway. They’ve started with the bathrooms. Elsewhere on the Qazaqfilm lot, the restrooms have already been renovated and now look presentable. According to acting president Aidar Omarov, all ten studio bathrooms were previously in such poor condition that they occasionally caused, as he put it, “misunderstandings” with producers.

A couple of corridors also look very presentable, with cleaner corridors and new linoleum.

Still, many parts of the studio haven’t caught up. Worn floors—some with holes—evoke the gritty feel of 1990s post-Soviet decline.

That faded atmosphere surfaced again and again as we wandered the grounds.

For many years, for some reason, funds received from the budget — flowing like a river —were never invested into Qazaqfilm. In theory, this should have created a solid financial cushion, at least enough to start basic renovations. But we are where we are. Now, through our own efforts and with the support of the Ministry of Culture, we’re carrying out minor repairs,said Acting President of Qazaqfilm, Aidar Omarov.

Qazaqfilm’s leadership is now aiming higher: plans are underway for a full-scale renovation of the studio complex. The goal is to finally move beyond outdated Soviet-era electrical panels, torn linoleum, and worn-out interiors. To make this happen, they hope to attract outside investment.

For more insight into the studio’s current direction and the broader state of Kazakhstani cinema, Acting President Aidar Omarov shared detailed comments in an interview with Orda.kz’s Editor-in-Chief, Gulnar Bazhkenova.

Restoring The Past

As we continued our tour, we moved to the sound studio building, which houses several editing studios. We were told that just the night before, editing work had gone late into the evening, and staff had been sent home to rest.

One bustling area was the restoration studio, where a long-term film restoration project has been underway for the past three years. It focuses on reviving classic films originally shot at Qazaqfilm but archived in Russia’s Gosfilmofond in Belye Stolby, near Moscow.

These films are now being purchased as digital copies and restored in Almaty.

To support the effort, Qazaqfilm acquired specialized equipment — computers and software — used by dedicated teams to clean up both video and audio. Depending on the condition of the source material, restoring a single film can take up to three months.

While we were there, a team was working on Shaken Aimanov’s iconic The End of the Ataman. They had already spent three weeks on it.

It's done like this: there are 10 of us, each of whom takes an average of 10 minutes of film and sits over them for at least two months. We remove scratches, dust, and sometimes even hairs that ended up on the film copy. Sometimes you have to sit over one frame for several days. And there are 24 of these frames per second,said restorer Ainur Baimurzina.

In addition to cleaning the film from visible screen debris, the restored copies are examined frame by frame. If any imperfections are spotted, the frames are cleaned again to ensure maximum quality.

On the second floor of the studio complex, sound restorers continue the meticulous process. These are specialized sound engineers whose job is to restore the audio of old films to their original quality.

They remove background noise, clicks, and other extraneous sounds. Their workspace is a mix of old and new — two modern monitors sit next to a console inherited from a 2011 upgrade.

However, restorers rely only on up-to-date computers and restoration software.

And their work is far from over. As restorer Ainur Baimurzina explained, before 1975, all film copies made in the USSR were sent to the Gosfilmofond near Moscow.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the rights to this vast archive, including Kazakh cinema classics, were retained. Even Kazakhstan’s first sound film, Amangeldy by Moisei Levin, is among them. Now, Kazakhstan buys back digital versions of these films for restoration.

These restored films are mainly intended for television broadcast. However, some have returned to the big screen. One example is My Name is Kozha, which was recently re-released in cinemas.

While it didn’t perform well at the box office, Acting President Aidar Omarov remains optimistic that future re-releases may find greater success.

Cinematic History

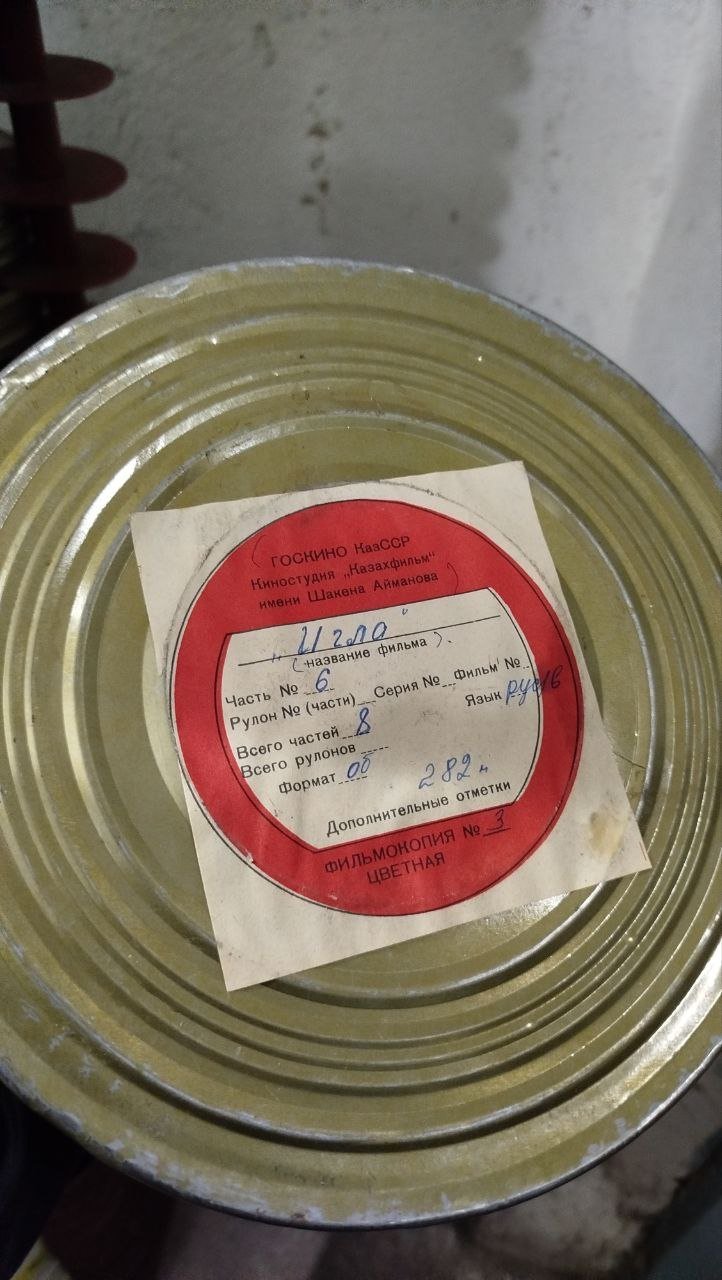

Not all Kazakh-made films are kept in Russia. At Qazaqfilm, we were given a rare look inside one of the studio's hidden gems: its film archive. Housed in part of a modest one-story brick building, the archive holds roughly 10,000 reels of completed works, ranging from feature films to documentaries and newsreels.

Alongside these are an equal number of original negatives, which can be used to restore a film if needed. Each reel contains approximately ten minutes of footage, preserving decades of cinematic history.

We have a chronicle here that dates back to 1939 and goes all the way up to the early 2000s — visits, official meetings, Nauryz celebrations — everything is preserved. We also have feature films up to 2015. After that, everything started being filmed digitally, and we haven’t received any new film since. says Svetlana Puzyrnikova, one of the curators of the film archive.

As Svetlana explained, some of the films stored at Qazaqfilm exist in only a single surviving copy. At the request of an Orda.kz journalist and longtime Viktor Tsoy fan, staff retrieved the film reel Igla (Ed. – Needle), which is preserved in the studio's archive.

Our journalist was allowed to briefly hold the reel before returning it to its storage location.

To preserve the archive, film copies are stored year-round at a constant temperature of 17 °C. Every three years, each of the 10,000 film reels is removed for ultrasonic and alcohol treatment — a whole cycle that never ends.

With this kind of care, Svetlana says, film can last for up to 300 years.

When asked whether the current storage setup at Qazaqfilm is ideal, Svetlana responded that it’s not bad, particularly because the national film studio has the infrastructure to support proper archival conditions. But, she added:

We preserve this heritage, we cherish it. But I would like a better conditions for it.

She pointed to Russia’s Gosfilmofond as an example, where films are stored in a dedicated, specialized building.

The films in Qazaqfilm’s archive are also being gradually digitized, although most of the restoration work is currently focused on movies that were stored in Russia. Svetlana believes that both film and digital formats should be preserved:

At some point, everyone decided to abandon film and switch to digital. But now many countries are returning to film again. In many, but not yet in Kazakhstan.

A similar digitization process is underway in Qazaqfilm’s sound library. Around 10,000 recordings are stored there, and about half have already been converted into digital format. The collection includes a wide variety of musical genres.

If you're just standing there, what should be playing? Of course, classical music. We have classical music. If you're working in a mine? Industrial music. We have that, too. We have classics by Kazakh composers. We have children's music. We have different genres. I myself went to Moscow and Leningrad for music. I took it from them. I didn't give ours to anyone! proudly shares music designer Akkaisha Baimuratova, who has been working at Qazaqfilm for 50 years.

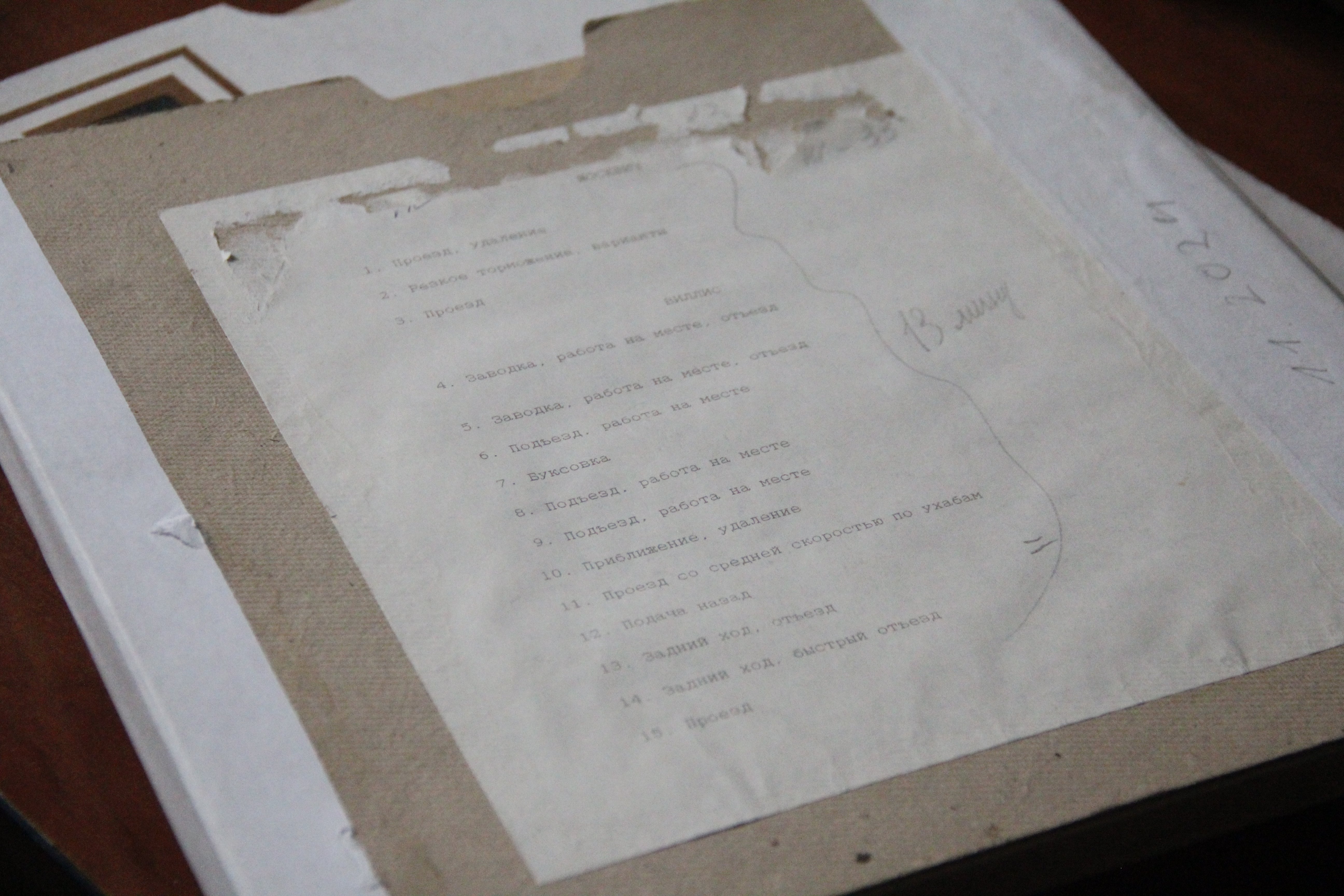

Secondly, in addition to music, the Kazakhfilm sound library also contains a collection of noises. For example, we were shown a reel featuring various sounds of Willys and Moskvitch cars, including the sounds of starting, driving, braking, and more.

All of this is converted into digital format using a computer and some device from 1981, which Akkaisha Baimuratova does not plan to give up.

A good device - either Czechoslovakian or Hungarian. It works well too. Why should I change it?she shrugs.

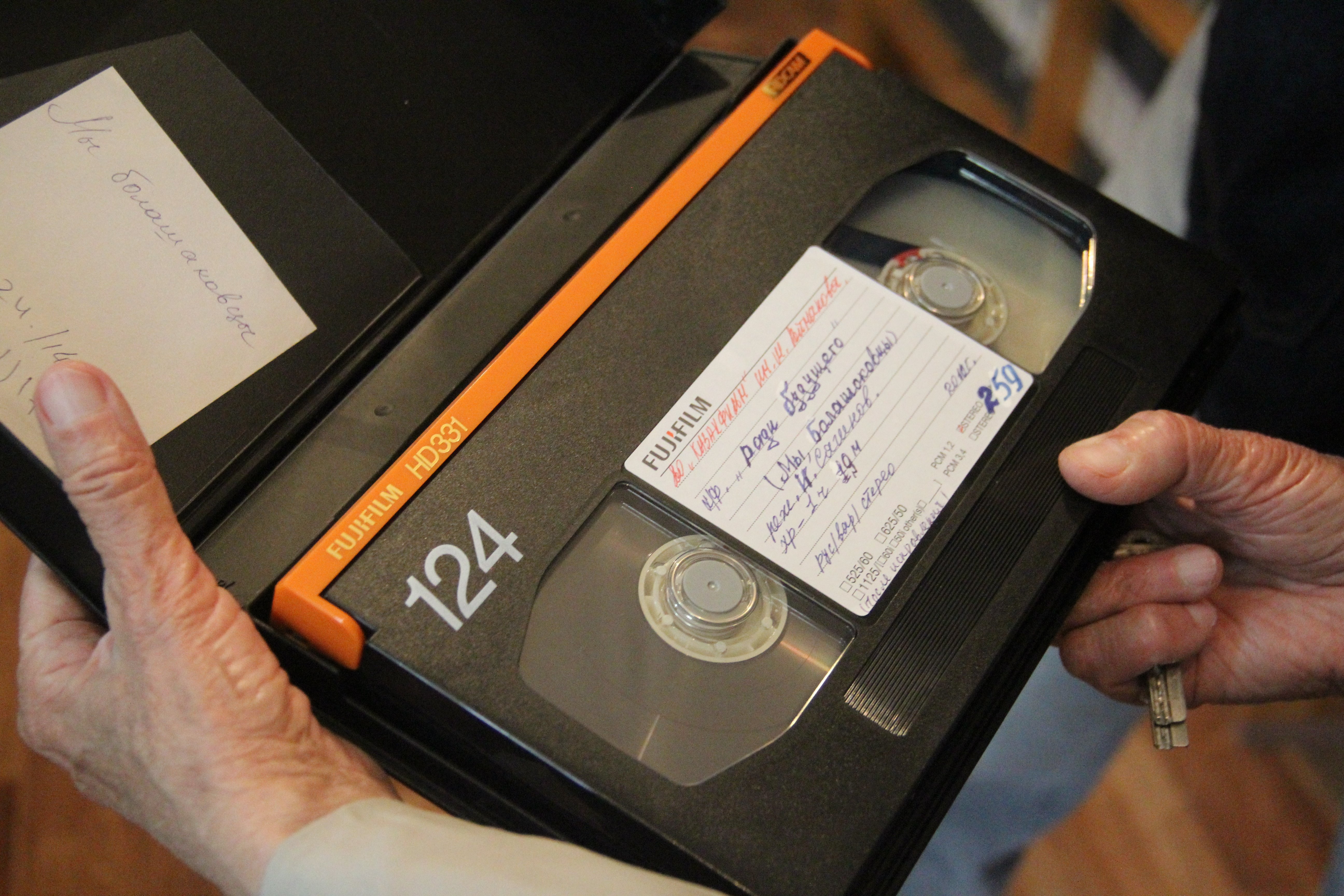

Akkaisha Baimuratova also maintains a video library, which she refers to as her savior.

This is a VHS collection featuring Kazakhfilm films. If suddenly the movie from the film library becomes unusable or, which is unlikely, is lost, then it can potentially be restored from a video cassette.

However, certain types of content cannot be digitized.

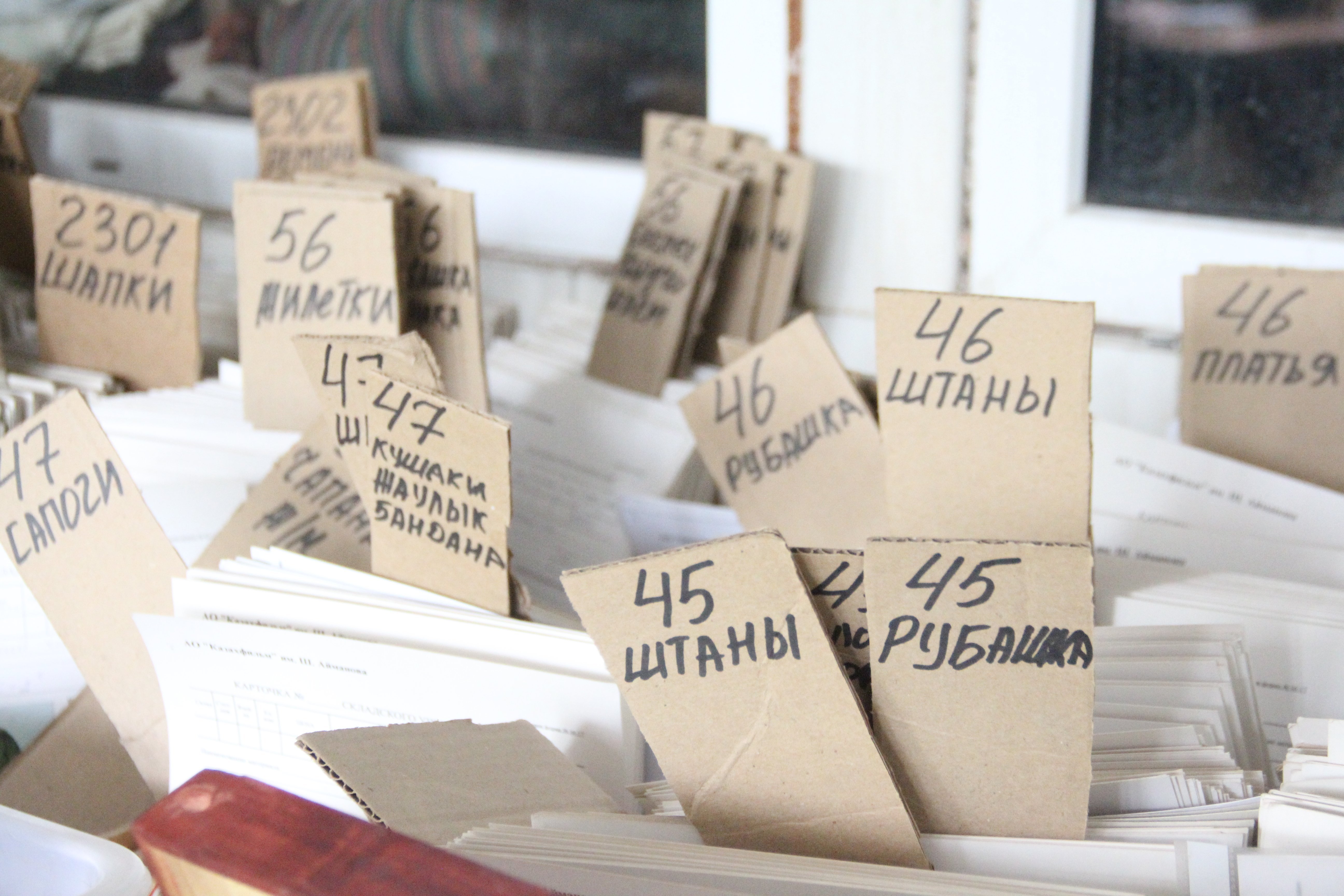

We were allowed to enter its domain — the costume room of national costumes. The props master, Gulzat Zhakupbayeva, keeps them.

It contains 5,000 items — from small earrings to khan outfits. Helmets of three types — metal, leather, and plastic- armor, clothing, headdresses, etc., are laid out on the shelves here.

As Gulzat says, much of what is presented here was made for the film “Nomad,” which was released in 2005.

Later, we used these costumes in many historical films — almost all of them after Nomad. They’ve even appeared in music videos. For instance, the 'Leila' video by Jah Khalib features our costumes. Same with 'Aidakhar' by Irina Kairatovna. By the way, renting costumes from us is even cheaper than renting animation props. Some outfits eventually wear out, and we send them to the scrap yard. But even those sometimes come in handy — for example, when we need costumes for beggars, where torn clothing is part of the look, says Gulzat Zhakupbayeva

These costumes also appeared in foreign films. For example, in the Egyptian series The Assassins, part of which was filmed in Kazakhstan.

This is not the only costume department at Qazaqfilm. There are others, each specializing in different historical eras.

When asked how much the studio's costume collection might be worth, Gulzat Zhakupbayeva couldn’t say.

But when we inquired about her salary as a prop master, she admitted she would like it to be higher. Other employees we asked about pay gave varied responses, ranging from "would like more" to "okay" and "can't complain."

According to acting president Aidar Omarov, what matters most is that salaries are paid regularly and on time.

Qazaqfilm no longer receives direct state funding; instead, it earns revenue from film production and renting out its pavilions and facilities.

Until 2019, Qazaqfilm received direct government funding for film production. Since 2019, when the State Center for Support of National Cinema was established, most of the funds have been redirected there. But thanks to the initiative of the Ministry and the decree signed by the head of state, 30% of box office revenues now go directly to Qazaqfilm,said Omarov.

More Light

Our tour continued to another Qazaqfilm building, which was partially rented by commercial companies and housed the AlmaU film school. Until recently, it also hosted Qazaqanimatsiya, now relocated to Astana. The signage and cartoon character murals remain as reminders.

In the same building is a hall used for color correction screenings, where near-final films are reviewed for accurate color rendering. The hall is occasionally rented out by other studios as well.

Here, we met video engineer Ayan Nurlankulov, one of the younger staff members at Qazaqfilm. He works with equipment acquired during the recent modernization effort.

From 2021 to 2023, we received dedicated funding to upgrade Qazaqfilm's technical base. As part of this funding, we purchased filming, lighting, and sound equipment, including cameras, dollies, and upgrades to several sound studios,said Omarov.

We concluded our visit where we began: the two-pavilion building, specifically in one of its storage rooms — the "light collector."

By chance, we met Andrey Machikhin, head of technical support, there.

He noted that approximately 40% of the studio’s lighting equipment is now modern LED, but this is no longer sufficient.

After COVID, a new generation of young camera operators joined us. They are used to working with LED devices. And about 60% of ours are old lens ones, mostly bought for the film 'Nomad.' New operators do not know how to work with them. And it turns out that we now have the technical ability to shoot about two films at once. But we’d like more, Machikhin said.

That phrase —"we’d like more" — surfaced repeatedly during our visit, as did mentions of the Nomad movie, whose 20th anniversary is approaching this November.

Original Author: Igor Ulitin

Latest news

- Trump’s Comments on Russia and China Surface in Audio Recordings

- Gollum and Two Stadiums: Comic Con Astana 2025 Opens in Astana

- Taraz Prosecutor’s Office Confirms Irregularities in Tender Process

- Chinese to Invest 70 Billion Tenge in "Underground" AI Project in Kazakhstan

- Thermal Power Plant Projects: Kazakhstan Looking for Alternatives for Russian Contractors

- Shymkent Theater Officials Accused of Embezzling Over 136 Million Tenge

- Ashgabat Responds to Media Report on Internet Access

- Rare Glimpse: Red-Listed Lynx and Secretive Badgers Filmed in the Wild

- Kairat Forward Becomes Youngest Kazakhstani to Score in Champions League

- Orda's Editor-in-Chief Targeted in Questionable Ownership Maneuver

- Businessman Tried to "Push Through" Astana Boiler House Project with a Bribe

- Foreigners Coming to Uzbekistan for Work Will Be Required to Take an HIV Test

- Toqayev Appoints New Director to Reorganized Anti-Corruption Body

- Former Employees of Key Witness Testify in Sarbasov Trial

- Kazakhstan Plans to Launch Direct Flights to New York, Tokyo, and Singapore

- Kazakhstan Expects Minimal Impact from U.S. Tariffs, Trade Ministry Says

- Hemp to Be Cultivated in Northern Kazakhstan for Industrial Use

- Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan Sign Series of Cooperation Agreements After High-Level Talks

- Vostokmashzavod Disputes Railcar Downtime Charges from KTZ-Freight

- Alik Aidarbayev Appointed General Director of Kalamkas-Khazar Operating