From Champion to Cleaner: Aisara Kerimbekova on Life After Sports and Training the Next Generation

Photo: Orda.kz

Photo: Orda.kz

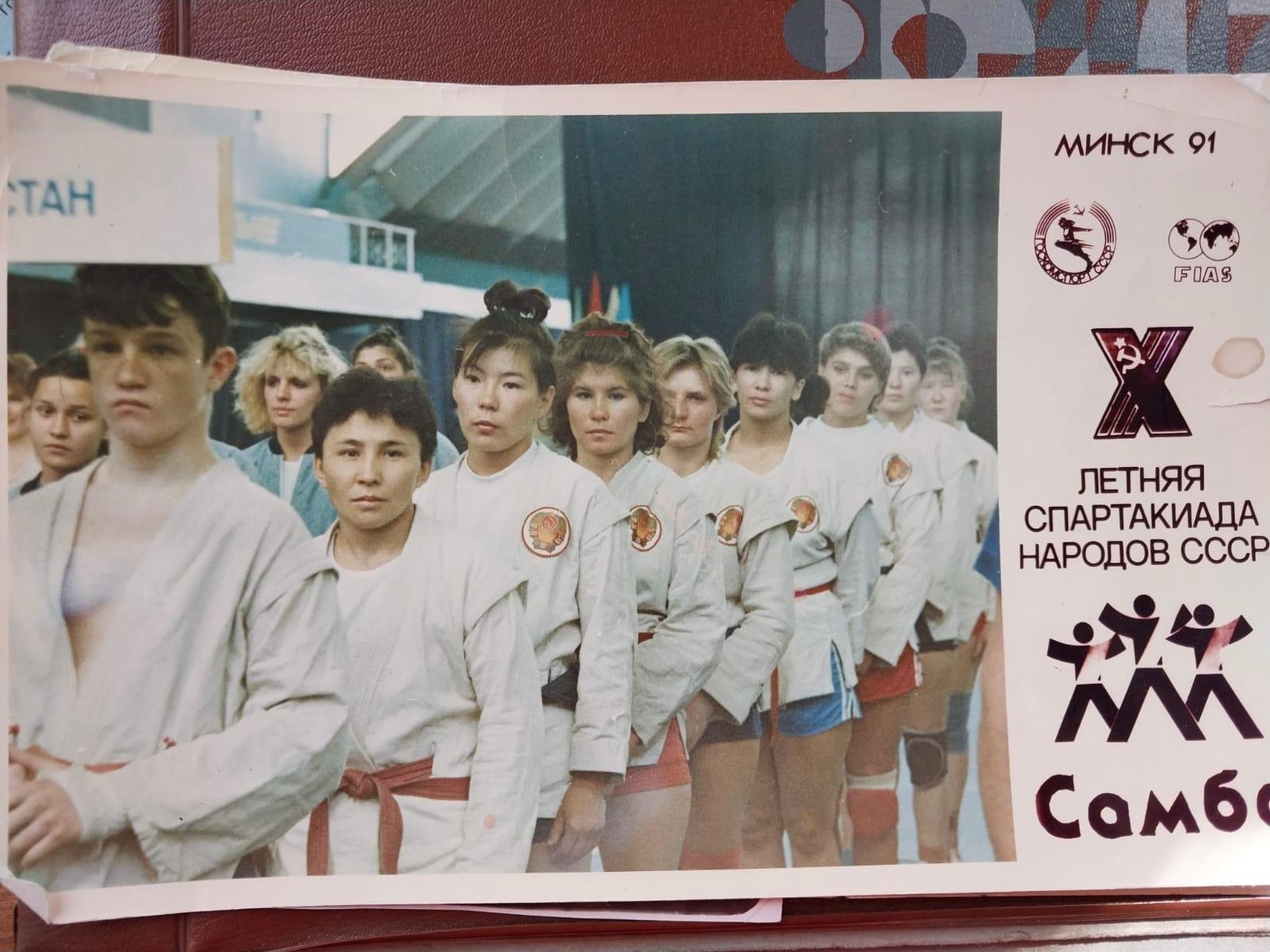

Aisara Kerimbekova is a Kazakhstani judoka and sambo wrestler who made her name in the 1980s and 1990s. She is a two-time silver medalist at the World Sambo Championships, an Asian champion, and a participant in the Spartakiad of the Peoples of the USSR.

But for more than 20 years, she worked as a cleaner while also serving as the chairperson of the housing cooperative and teaching physical education. Now, Aisara plans to leave this taxing work behind and focus on training young athletes.

We spoke with her about life after sports and what helps her keep going.

O: Aisara, how did you get into sports? Why did you choose sambo and judo?

A: Since childhood, I ran and wrestled with boys. I loved sports — but not volleyball or basketball, I loved wrestling. My father was a wrestler, and so was my mother. We grew up watching them. In the village, on the grass, on bare ground, we wrestled all the time.

After school, I helped my brother in the village of Sharbakyn, where he herded cattle. Then he got a job at Dynamo in the city. Another relative of ours was the head of Dynamo, and so my brother offered to introduce me there. He said, “This is not a boy, this is my little sister.” Then they decided: “If so, women’s wrestling is opening, let’s bring her.” That's how I got invited.

When I came to the gym, the coach at first thought I was a boy. There were few girls, so I trained with the boys. I would change clothes somewhere, then come back and wrestle again. In the village, at tois (celebratory events in Kazakhstan - Ed.) or while shearing sheep, we always wrestled.

My uncles would joke: “Are you going to wrestle? Well then, wrestle!” And I did — with boys my age, younger, and older. That’s how I got into sports and chose judo. Back when women’s judo was just starting, there weren’t many of us.

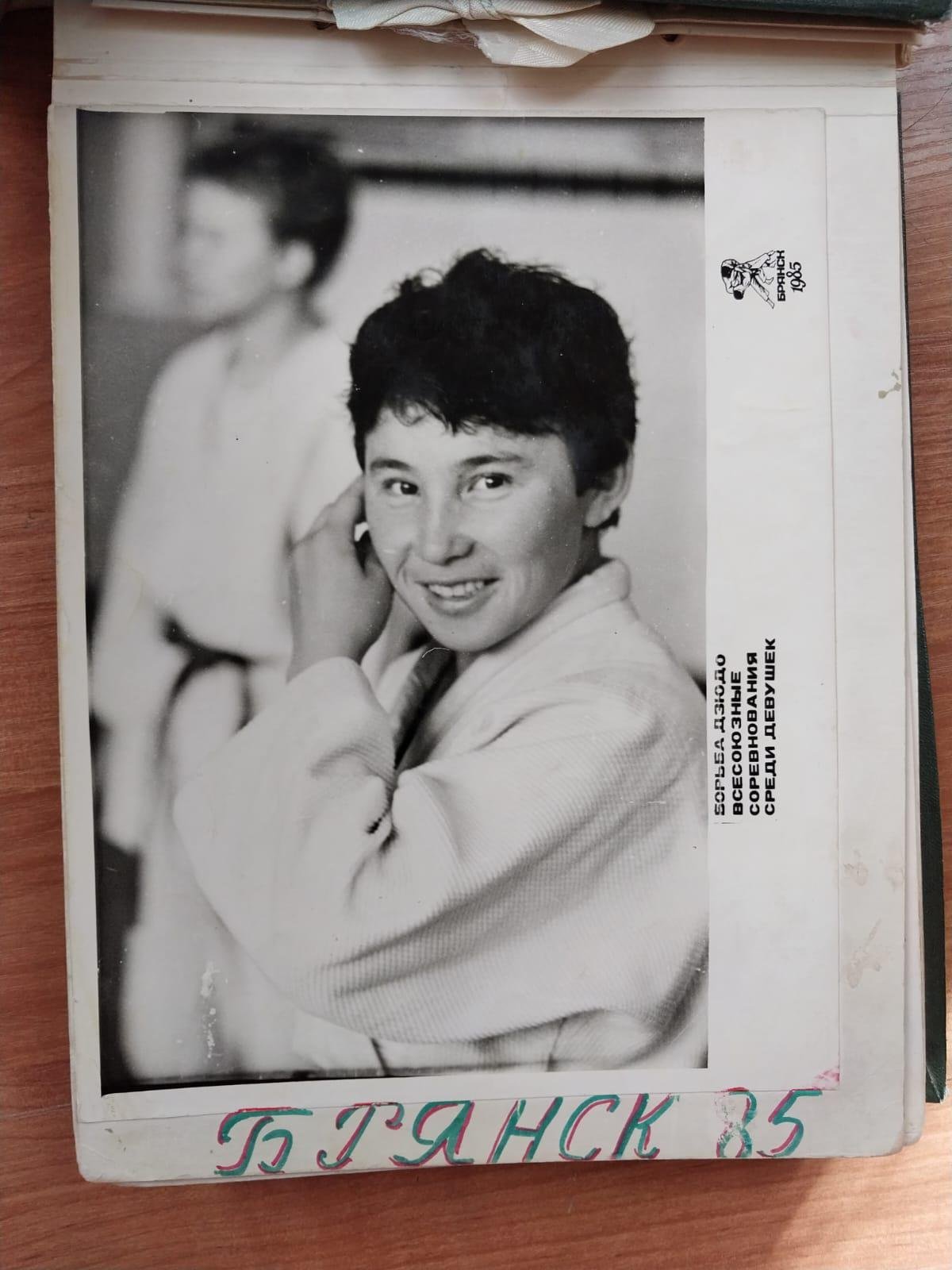

After 15 days, I was handed over to Kaim aga. His real name was Abylkhair Abylkhanovich Baybolsyn, but everyone called him Kaim. He was my first coach, and with him, we began serious training. Then we went to the championship in Bryansk, where I took second place.

I was leading on points but lost to a girl from Uzbekistan, Zigantina, because we hadn’t been taught choke techniques yet. But I had all the points. Later, we learned that, too. That’s how I became an athlete.

O: What memories do you have of Spartakiads and world championships? What mattered more — the medal or representing your country?

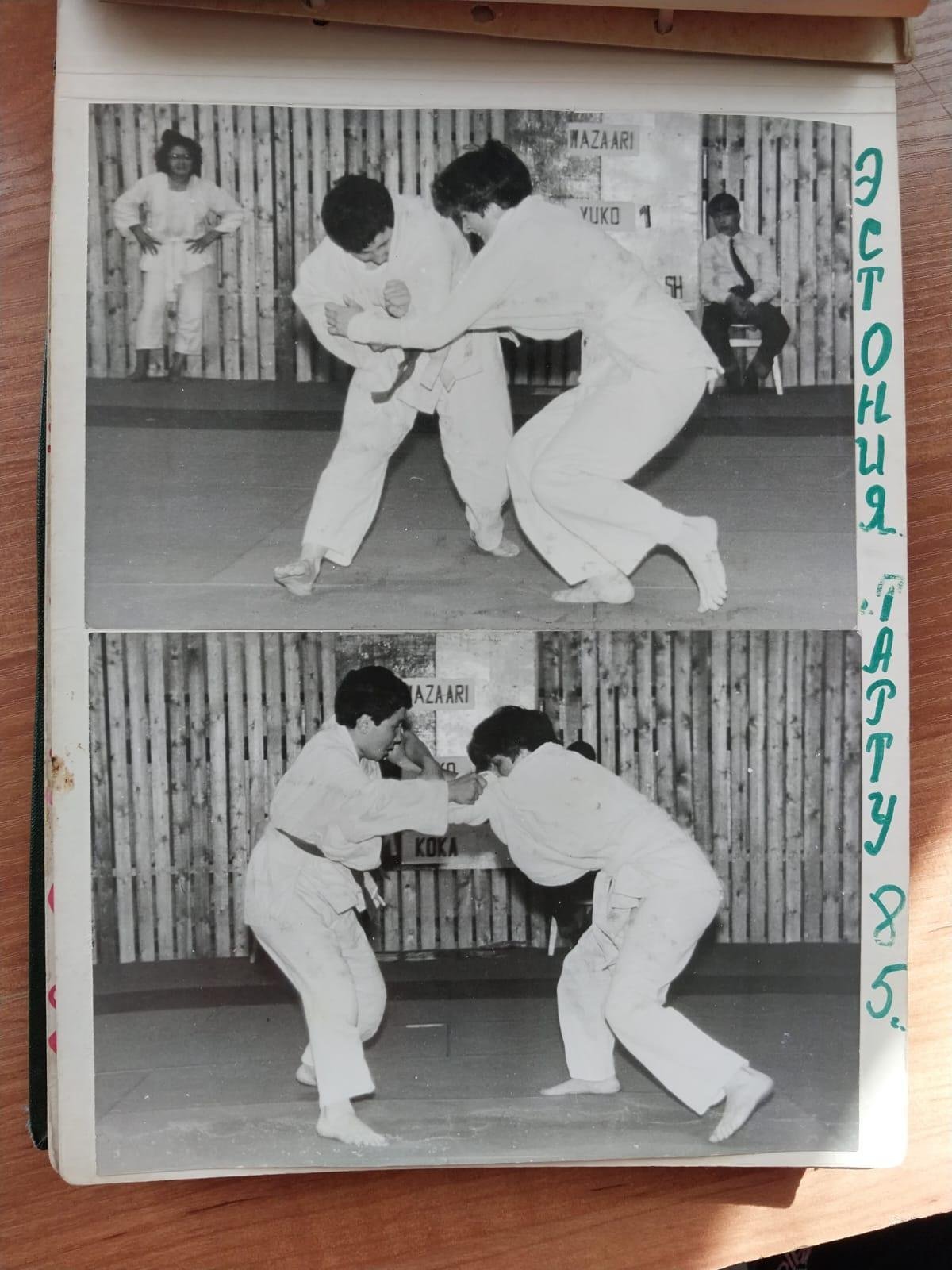

A: It was hard during the USSR. To go abroad, you first had to win the Union competitions. I remember competing for Dynamo, and later, there was Estonia. At that time, I didn’t speak Russian, and judo commands were in Japanese.

They would say “yuko” or “koko,” and the coach would shout “hold on” — so I would grab, drop from my knee, and throw. It was similar to Kazakh wrestling. I liked everything. I loved both judo and sambo. Those were bright moments.

The Union anthem was played in the Soviet days. And now, when our young athletes raise Kazakhstan’s flag to our anthem, I feel proud of them. May they rise higher and higher!

For me, medals were never the main thing — it was about honor. As they say: “Yerdi namys öldiredi, koyandy kamys öldiredi” (Honor kills a man, and reeds kill a hare). Since the state was paying, I had to justify the bread I ate.

That’s why I fought not for myself, but for my country. I had to win and bring back a medal — it was my duty.

O: How did life turn out after your sports career? What did you do?

A: I didn’t quit sports right away. I kept wrestling for a while, then I had a child. It became hard to raise a child without help. So I decided to earn my living honestly, even if it was physical work. I worked as a teacher, a chairwoman, a cleaner, and a gardener.

I trimmed trees and put everything in order myself. The main thing is honest work. I feed my children with the sweat of my brow. As they say: “You may be in a hurry, but Allah is not in a hurry.” Thanks to my family for helping me.

I’m grateful to the people of Kazakhstan.

O: Did the state, federations, or sports organizations provide support?

A: Only Nurkadilov gave me a one-room apartment, and I live in it. Unlike children today, we weren’t even given refrigerators or TVs — only paper certificates and metal medals. And we were happy with that, too.

O: When did you feel that the government and society had forgotten you?

A: Probably they have… But what can you do? We’re still alive. My daughter-in-law, Anna, posted a video on TikTok for my 60th birthday, and people began to notice me again. I thank her and everyone who supports me. May she be happy.

O: What is your day like now?

A: Everything is the same. I wanted to quit my menial job. After the TV broadcast, many people were upset: “How can such a deserving woman be sweeping the streets?” I’ll work until the end of the month, and then, God willing, I’ll leave. Now I work as chairperson of the KSK — pipes, basements, preparing for winter.

I was invited to the Bauyrzhan Momyshuly College at CSKA. I want to help young people — if not as a coach, then as a mentor. I do my exercises in the morning, then I do my housework.

O: Have you been invited to sports schools as an experienced mentor?

A: No. Even though I’ve been working at the college for 12 years, nobody has invited me. But I still work — I take students to competitions. My students have taken first place in Togyzqumalakq and checkers. Recently, my boys took second and third place in freestyle wrestling.

This is my contribution. I believe this is how I help my people.

O: What helps you not give up in difficult times?

A: I want to live. I have a son — a gift from Allah. I want to babysit my grandchildren. My brother Sharbakin has six children, and they already have two great-granddaughters. When they run up to me shouting, “Apa! Aje!” (Grandma –Ed.) — how could you not want to live after that? They are my blood.

My grandchildren call me “muscle boy apa” as a joke. Let them be happy. I dream that my son Daniyar will get married, and that his first child will be a daughter — a wrestler like me.

O: Were you surprised by the support on social media? How did it make you feel?

A: I was very happy. As they say, “Gold has no price while it is near.” People have helped — some gave 20 thousand, some 10, some a thousand. I thank the Kazakh people and everyone in general. Recently, they even brought me a gas, a washing machine, and an air conditioner. Thank you very much.

O: The Ministry of Sports said they are compiling a list of veterans. Have they contacted you?

A: Yes, they’ve been calling for two days now — both from the region and the city. I want to believe that now they will remember us. I’m not sitting idle — even though I have less strength now, I have experience. We can still train the younger generation.

O: What would you say to young athletes today?

A: I teach at a college myself. Some students don’t even want to put on a sports uniform. They say, “Why do I need this?” I tell them, “It’s for your health!” It’s better to play volleyball, football, or checkers than to sit on your phone all day.

Now the facilities are great — gyms, showers… Back in our day, we trained in basements without even hot water.

O: What would you say to the minister, the Akim, and the heads of sports federations?

A: Let them remember people like us. Not just me — there are many of us. We are sports veterans. Once there were war veterans, now there are us. Let them at least invite me as a guest — to say a few words and inspire the youth. The sambo community recently congratulated me and gave me a horse. Thank you! Let them not forget their elders.

O: What quality do you consider the most important in yourself? Do you have any unfulfilled dreams?

A: The most important thing is humanity. Life is short. Nowadays, even brothers don’t respect each other because of money. I never chased wealth, but I thank God for my health. I hold no grudges. But when I see young people sending their parents to nursing homes, my heart aches.

I have been an orphan since I was seven, so such things hurt me especially deeply.

I have one dream — for my son to get married and for me to babysit my grandchildren. To take my granddaughter by the hand to the gym.

I want my father’s name — Kerimbek — to be heard again.

Original Author: Nurtore Zhumagul

Latest news

- Kazakhstan Explains How Russians Who Fled Mobilization Can Be Deported

- Kazakhstan and Japan discuss hydrogen partnership with export potential

- Russia Thanks Tokayev for Initiative to Support Russian Language

- Almaty Could Restrict Cars Under Beijing-Style Anti-Smog Plan

- Tigers in Kazakhstan Are in No Rush to Breed

- What Changes Are Being Prepared Under the New Tax Code

- Alcohol and Tobacco Prices in Kazakhstan See Sharpest Monthly Rise in 15 Years — Analysts

- Middle East Conflict Will Not Lead to Higher Gasoline Prices in Kazakhstan — Minister

- Five Regions of Kazakhstan Face Higher Flood Risk This Spring

- Kazakhstan Ratifies Turkic States Civil Protection Deal

- Astana Enters Top 100 Safest Cities as Smart City Project Expands

- Almaty Cameras to Record New Driver Violations Starting March 12

- Kazakhstan Suspended 11 Polling Stations Abroad Due to Middle East Escalation

- Kazakhstan’s Foreign Ministry Comments on Disappearance of Citizen After South Korea Factory Fire

- ChatGPT Among AI Tools Recommended for School Lessons in Kazakhstan

- Missing Kazakh Woman Found in Vietnam Four Days Later

- Seven-Year-Old Kazakh Girl Returned From Georgia Following Six Months of Diplomatic Efforts

- Kazakhstan Plans to Rent 11 Helicopters for 22 Billion Tenge Ahead of the Fire Season

- Flights Delayed and Canceled at Astana Airport Due to Bad Weather

- More Than 8,500 Kazakhstanis Evacuated From the Middle East