"We Are Considered Rejects of Society": How Those Incarcerated Adapt

From 9 to 16 thousand people leave the colonies in Kazakhstan every year. However, not everyone can return to their usual life. Those formerly incarcerated are denied jobs and abandoned by loved ones. Society also looks down on them. Meanwhile, there is no unified system of re-socialization for them in Kazakhstan, nor is there a law for its regulation. As a result, most formerly incarcerated individuals commit crimes again. Orda.kz has looked into possible solutions.

Served Time for Homicide, Now Going to Open a Business

Social adaptation for those who have been incarcerated is necessary, says 51-year-old Svetlana Kaverina. Svetlana served nine years for killing her friend's husband in 2014.

The story, no matter how sad it may sound, is typical for Kazakhstan. In 2014, I was visiting a friend. Her husband came in late at night, either drunk or high, and started beating her. Later, he came after me and their one-and-a-half-year-old child. We tried to stop him, but he was much bigger than us. He could have beaten the girl to death, so I grabbed a kitchen knife and stabbed (him - Ed.).

Svetlana's actions were assessed in court as homicide, not self-defense. According to her, 96% of incarcerated women serving a sentence for homicide were defending themselves from aggressors.

This was my first conviction. After the verdict, I felt angry and offended. Days in custody went by the same way. But I had to put up with it. I worked as a construction worker in prison and was looking forward to seeing my loved ones. But, not all of them treated me the same as before: my sister disowned (me - Ed.) and turned my eldest son against me. So, when I was released in April 2023, I went to my youngest son, who already had his own family and children.

Svetlana missed the wedding of her youngest son, the birth of grandchildren, the death of her mother, and how little Zhenya grew up, whom she saved nine years ago.

Svetlana admits that she was scared and didn't know where to go after serving her sentence.

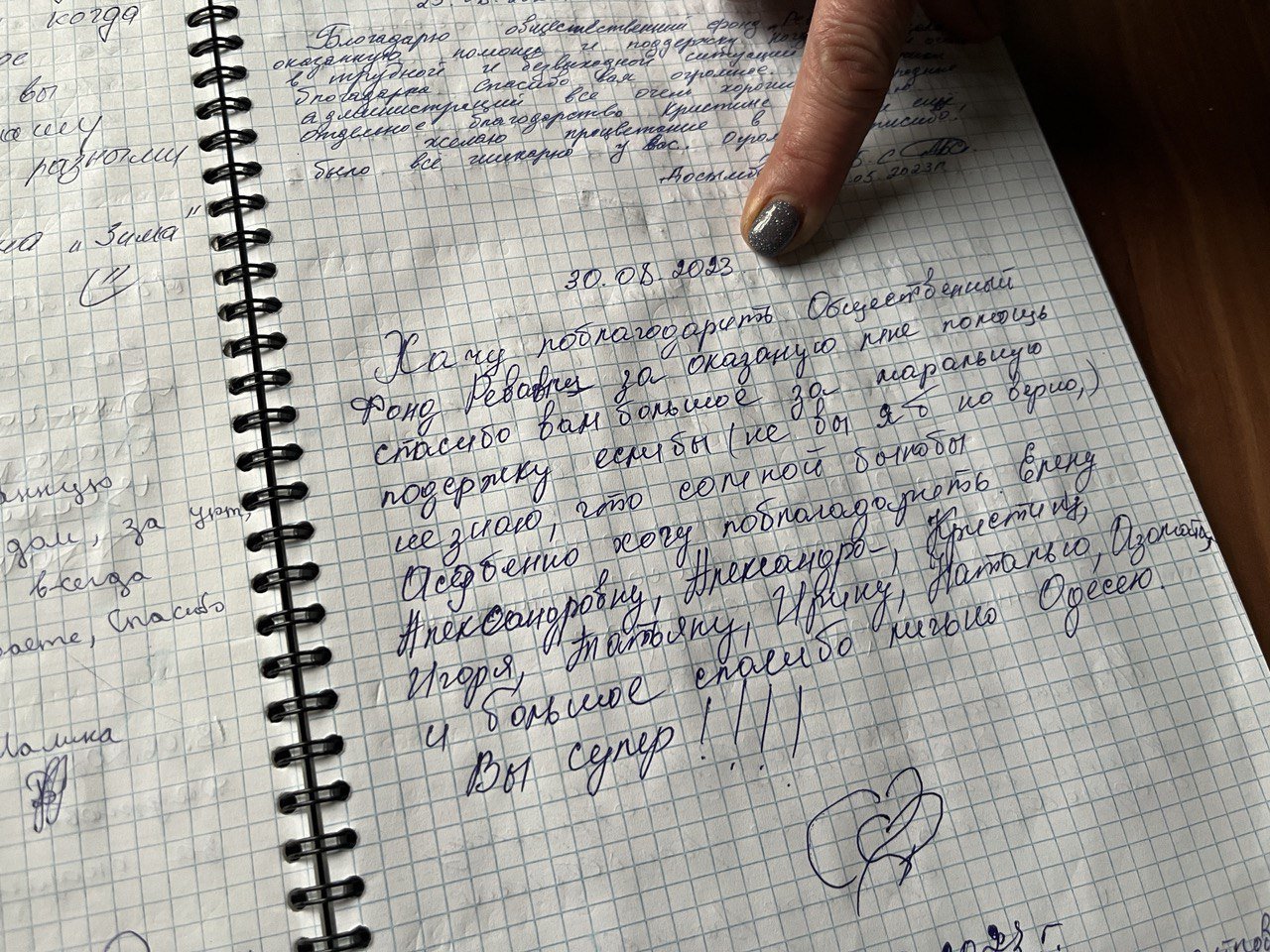

Svetlana's son sent her to the "Revansh" adaptation center, where she lived and underwent rehabilitation for six months. There she was provided not only with legal and moral assistance but also received help with registration and job-hunting.

Svetlana currently rents an apartment, works as a dishwasher, and plans to open her own business: a construction company where formerly incarcerated persons will work.

She believes that her plan can help them believe in themselves again and start a new life.

We Help Those Forgotten

However, not all those who have been incarcerated are as lucky as Svetlana. According to Kuat Rakhimberdin, Doctor of Law, member of the Public Council on Internal Affairs of the Republic of Kazakhstan, 40% of them become repeat offenders in our country. According to the expert, this happens for several reasons:

- Changes in a person's psyche after imprisonment

- Inability to live independently

- Lack of effective social reintegration mechanisms

- Preservation of the influence of a criminal subculture

Kazakhstan has a probation institute, which, according to global standards, should be aimed at laying down the foundation for social reintegration. It turned out differently in Kazakhstan, though.

Our country was the first in the Eurasian space to create a probation institute and adopt an appropriate law. However, it turned out, as the saying goes: "It was smooth on paper, but they forgot about the ravines (Russian equivalent of “It looks good on paper” - Ed.).” These "ravines" are a system of re-socialization. To date, there are neither clear and meaningful programs nor an algorithm for their compilation and application. The probation system is underperforming, and its staff failed to build an effective and scientifically sound process for the re-socialization of incarcerated persons, the expert believes.

The issue of reintegration has been transferred to local executive bodies. According to Rakhimberdin, such artificial separation will not help formerly incarcerated individuals to reintegrate into society.

It is a paradox, but officials of the departments of employment coordination, who have never worked with those convicted of a crime, are invited to re-socialize them. What, then, should probation authorities do? Control those convicted? It turns out that control and the tasks of re-socialization were artificially separated, says Kuat Rakhimberdin.

On January 29, 2024, information surfaced that The Committee of the Criminal Executive System of the Ministry of Internal Affairs wants to amend the order "On the rules of educational work with prisoners sentenced to imprisonment." The relevant amendments were published on the Open NPAs website. Public discussions will last until February 12.

According to the amendments, if a person convicted of a crime does not have a home or the opportunity to live with relatives, the colony administration must inform the local akimat two months before their release. Akimats will be obliged to inform a colony’s administration within 15 days about the "possibility of providing housing or lack thereof." If there are no places in the re-socialization center, then they will be offered to choose another nearby area.

This is the first initiative aimed at finding housing for those convicted. While the authorities are considering amendments, public funds are taking over this function.

The Revansh Foundation in Almaty is among the few of them.

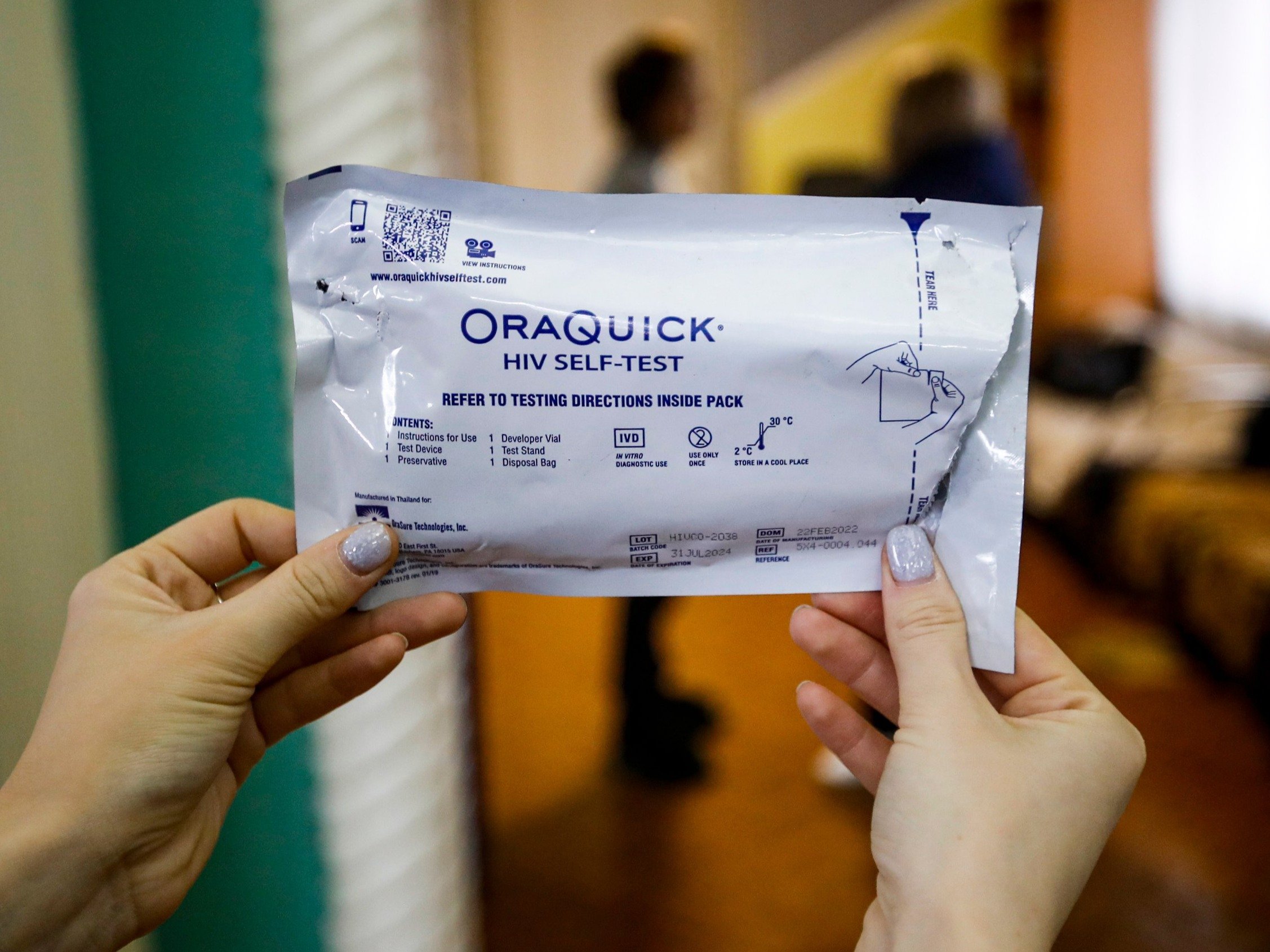

“Revansh" has been helping formerly incarcerated persons, people recovering from addiction, those living with HIV, and others for six years.

There are centers in the country where women who have experienced violence can apply, but what should the rest do? For example, when a woman is released from the colony, she simply has nowhere to go. The state does not pay attention to former prisoners at all. And as a result, this leads to even greater criminality. Imagine: here is a man released from prison; but where will he go if he does not have a place to live and a registration? Making trouble again? Believe me, no one who is there dreams of such a thing, says Elena Bilokon, founder of the foundation.

Bilokon did not serve a sentence. She, however, discovered that she was HIV-positive in 1996.

Elena hid this for 10 years. She later began to help people. She initially led the crisis center in Temirtau and then "Revansh". She says she has dedicated her life to helping those "whom the state has forgotten.”

The fund currently employs 54 social workers. Most of them are peer counselors: formerly incarcerated persons, those who have recovered from addiction, and people living with HIV.

A married couple, Kristina and Igor, have been working at Revansh for five years. They visit all the colonies of the Almaty region, explaining that there is life after prison.

We hold mini-sessions in colonies, share experiences to motivate people to build new thinking and lifestyles. I was in prison for a total of 14 years for drugs. So, I understand with what trepidation those convicted are waiting to be released. So, when I come to the women's colony, I want to show the girls that people are waiting for them on the other side. We are waiting, says Kristina.

The rented two-story building of the Revansh Office accommodates 10 women. Here they can obtain registration, undergo rehabilitation, and receive legal assistance along with weekly sessions with a psychologist. Social workers together with the guests arrange performances and theater shows once a month.

The maximum period for which women can stay is six months, but women occasionally get back on their feet faster.

The organization does not turn men away, but it cannot offer them a place to stay yet.

Hundreds of people come to us, some of them are men. We help them with their documents, but we can't offer them lodging. We have been trying for years to get our own building set aside for us. This is our sixth move during our work. After all, the house can be sold at any moment, and people will end up on the street.

Neighbors Tried to Evict Us

The building provides not only lodging for formerly incarcerated persons for re-socialization but also the ability to register them for further job-hunting through an employment center.

Finding a home, as Bilokon notes, is a difficult process, but it is even more difficult to deal with the social stigma.

I remember when we lived on Shemyakin Street last year, the neighbors raised a ruckus to evict us. They planted drugs, shouted that they would burn us down along with the house, and called the district police officer. But we had done nothing. We eventually had to move out because the owner sold the house. We live in peace in our current place. After all, as soon as we moved in, we got to know the neighbors and explained what we were doing, says Bilokon.

The opening of the Answer Adaptation Center did not come to fruition in Oskemen along similar lines. In 2014, a small house appeared on the city outskirts next to the Druzhba cottage cooperative. People who had just been released from prisons were supposed to live in it.

The residents were opposed, however. They did not want to live next to former prisoners. People started contacting various authorities with requests to inspect the center. The court decided to demolish the building. 10 years have passed, and Answer still has no building to accommodate people.

Stigma also causes people to hide their past.

Tatyana Eroshkina was brought up in an orphanage. She was released on parole in 2023, has been undergoing re-socialization at the Revansh Foundation for five months. She has been working as a cleaner unofficially and does not speak about her criminal record with her colleagues and employer.

I was in prison for drugs for two years. This is my past, for which I have already done my time. But our system is such that a convicted person will not even be given a rag in their hand. That's why I won't admit it, otherwise they'll part ways with me. We are considered the rejects of society. It hurts me when colleagues talk about prison and convicted persons. I don't answer them, I try to be silent and swallow (my pride - Ed.), no matter how insulting it is, shares Tatyana.

Two Options: A Rag Or A Rag

According to the Ministry of Internal Affairs, as of September 2022, 11.6 thousand people were employed in colonies. 241 small and medium-sized businesses provided them with work. They produce many things: from house slippers and food to building materials and furniture. Their pay — from 25 to 80 thousand tenge (roughly $50 to slightly under $200). Some of this money, upon necessity, could go to cover inmates’ debts.

But after prison, the choice of work for former inmates is scant. Tatyana Eroshkina says: "We have only two options: a rag or a rag."

Most former prisoners work unofficially despite the jobs not requiring qualifications. Getting a job with reasonable pay through a social security program is no easy task.

Informal employment is sometimes fraught with dishonesty and non-payment of wages.

The solution to the problem may be jobs with a quota for former prisoners.

This idea was voiced in 2015 by Svetlana Zhakupova, Vice Minister of Labor and Social Protection (now Minister). She suggested that law enforcement officers put together lists of those who will be released in the next six months and send them to the Ministry of Labor so that they could have jobs ready for them.

But nine years have passed since. There has been no news about such enterprises.

World experience shows that this practice works. In the United States, there is a Work Opportunity Tax Credit (WOTC) program that provides tax incentives to companies that hire certain workers, including those formerly incarcerated. This encourages businesses to hire those who may find it difficult to find work after serving their sentences.

The state of Michigan has a 30-2-2 program: 30 companies hire two formerly incarcerated persons and track their progress for two years. The results showed that in the first two years — from 2014 to 2016 — 1,709 people were employed through the program.

In the United States and the United Kingdom, the Ban the Box initiative is in place to remove the matter of criminal history from the initial stages of the recruitment process so that it is easier to qualify.

Common methods include tax incentives, training to improve the skills of former inmates, as well as partnerships with organizations specializing in the reintegration of former prisoners.

As in the case of social adaptation, Revansh plans to take the solution to the employment problem into its own hands. Elena Bilokon said that the foundation plans to open a social cafe and a hairdresser, where the guests of the adaptation center will work.

This will allow us to employ our people, adapt them to life in freedom. It will also help the foundation to pay for the rent of the building simply. After all, we do not have funding from the state.

Cheaper than Prison

"Revansh" has been operating for six years with the help of donors, international organizations, and grants. Currently, the main sponsor of the fund is the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime.

Of course, various organizations help us, even some deputies. But this is incompatible with the amount of work. We participate in state competitions every year. One year there may be a grant, and the next it is no longer there. Now think about how one can go about this. At the same time, even representatives of law enforcement agencies bring people to us. This proves that our services are needed at the state level. But the authorities do not want to pay, Elena Bilokon says.

According to lawyer Dauren Mombayev, the authorities are not interested in allocating a budget due to functional illiteracy and stigma surrounding former inmates.

Due to the negative attitude towards former inmates and the narrow-minded campaign, the authorities do not consider it necessary to allocate a budget for their adaptation. While allocating large resources for criminal repression. However, from an economic point of view, the adaptation of former inmates will cost taxpayers less than keeping them in prisons.

In 2022, 34,702 people were in institutions of Kazakhstan’s penal enforcement system. 6,567 were in pre-trial detention centers and 28,135 were in correctional institutions. Almost 58 million tenge was allocated for them.

The state spends about 1.6 million tenge for each prisoner or prisoner. That is, a little more than 139 thousand per month.

Expenses include food, medicines, clothing, bedding, and hygiene products. Utility bills are being paid separately, as well as escorting and traveling to the destination of those who have been released.

From the Editorial Office

The Revansh Foundation believes that their work will help people successfully adapt, at least those ready for positive changes.

They are actively developing recommendations for the government on re-socialization, calling on deputies to consider supporting formerly incarcerated persons during election campaigns and looking for a suitable place for those who need help. The goal is to provide them not only with housing but also a safe place from where they will enter a new world.

This material was created in the genre of decision journalism within the framework of the Solutions Journalism Lab project.

Original Author: Silam Aqbota

DISCLAIMER: This is a translated piece. The text has been modified, the content is the same. Please refer to the original piece in Russian for accuracy.

Latest news

- President Toqayev Sends Nazarbayev Birthday Wishes

- Toqayev Appoints New Ambassadors in Series of Diplomatic Changes

- Unidentified Object Resembling Drone Found in Atyrau Region

- Trump and Zelenskyy Discuss Air Defense Needs

- Rapper Qurt: Wife Withdraws Statement in Court

- Head of Azerbaijani Cultural Autonomy in Moscow Region Reportedly Loses Russian Citizenship

- Defense Secretary Hegseth Paused Ukraine Weapons Shipment Despite Pentagon Assessment — NBC

- Prosecutor General's Office Confirms Detention of Kozhamzharov's Associate in Torture Case

- State to Scale Back Role in Competitive Sectors

- Uzbek Banker Kidnapped in Paris

- Former Financial Police Officials Reportedly Detained, Case Concerns Torture

- Progress MS-31 Launches from Baikonur Carrying Fuel, Water, and Scientific Cargo

- Two Men to Face Trial for Homicide of Missing Atyrau Woman, Body Not Found

- Russia Launched Massive Strike on Ukraine Following Trump–Putin Call

- Rapper Qurt Accused of Abuse by Wife

- Pavlodar Region: Rescuers Seek Lower Retirement Age Amid Strain of Risky Work

- Businessman Vagif Suleymanov Detained in Moscow

- Kashagan Field Reaches One Billion Barrels of Oil Extracted

- Lenin Street in Osh Renamed After 19th-Century Kyrgyz Leader

- New Uranium Plant Launched in Turkistan Region with French Partnership