How Saiga Antelopes in Kazakhstan Went from a Sacred Symbol of the Steppe to Becoming Problematic

Photo: ACBK

Photo: ACBK

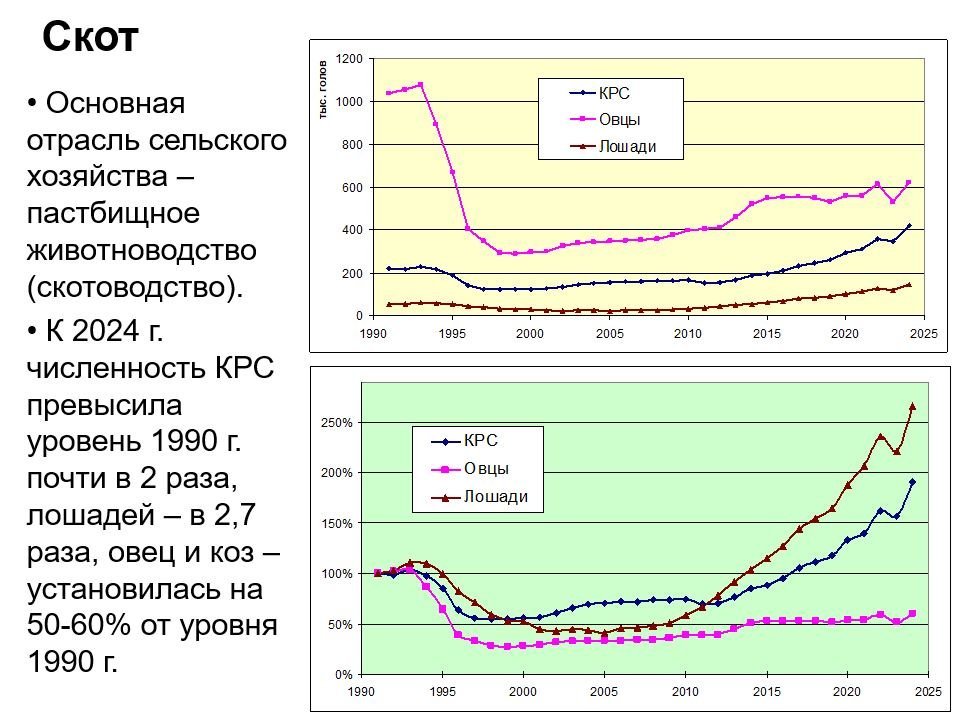

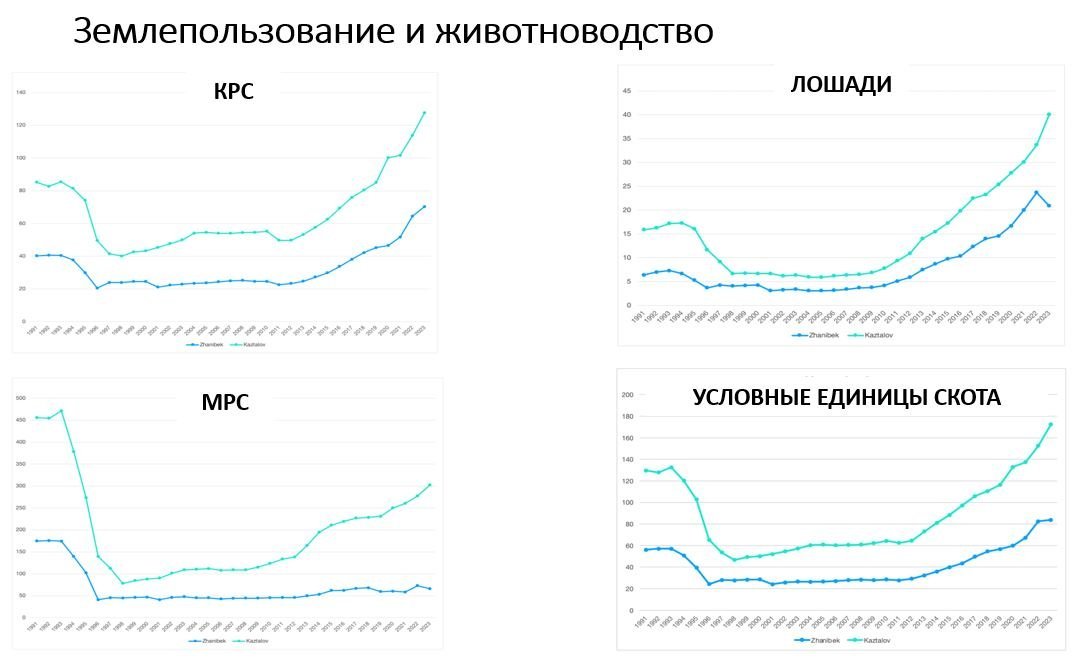

In recent years, the Ural saiga population has rebounded and surpassed historical levels. Meanwhile, the region's livestock numbers and farm sizes have been steadily increasing, encroaching on the saiga’s traditional habitat, Orda.kz reports.

This issue was a key topic at the recent regional scientific and practical conference Human-wildlife conflicts in Central Asia held in Almaty. Organized by the Institute of Zoology of Kazakhstan and Germany’s Michael Succow Foundation, the event dedicated a session to the ongoing tensions between steppe antelopes and rural communities in West Kazakhstan, particularly livestock farmers.

Farmers have long voiced concerns about the increasing saiga population, claiming the antelopes consume crops, trample fields, and deplete water resources. In response, the government briefly approved a limited culling of saigas last year.

However, this decision sparked public outcry, and the program was quickly abandoned. Rumors spread that saigas were not significantly harming farms and that the culling was intended to facilitate the sale of saiga horns to China.

To clarify, the Association for the Conservation of Biodiversity of Kazakhstan (ACBK) has been conducting extensive research in Western Kazakhstan. Their findings paint a complex picture of agricultural expansion and its impact on wildlife.

Since 2000, the human population in the region has declined by about 23%, yet the number of farms continues to grow.

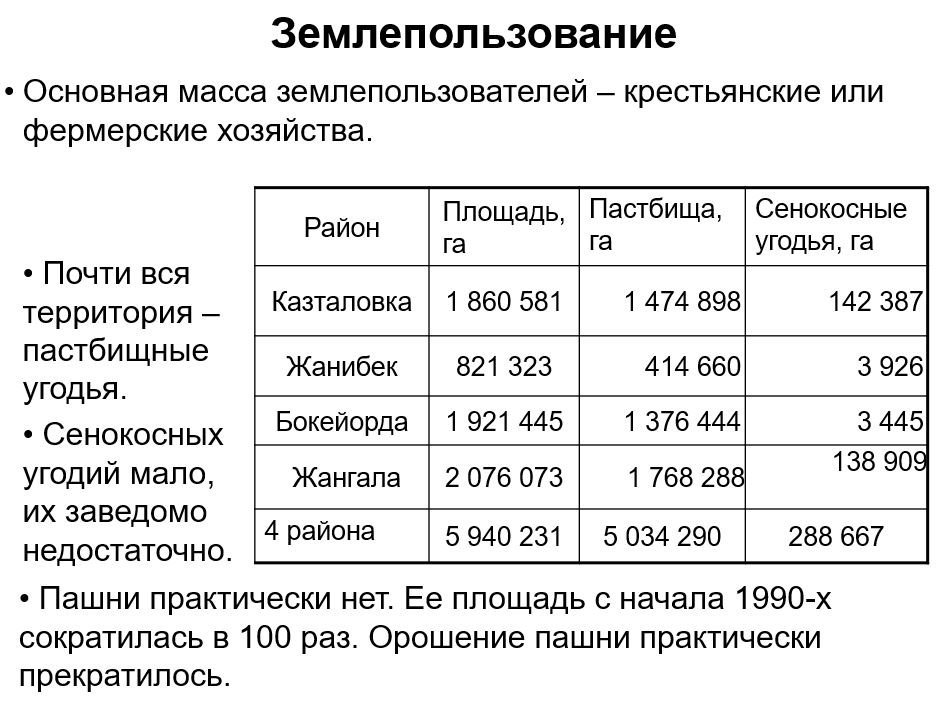

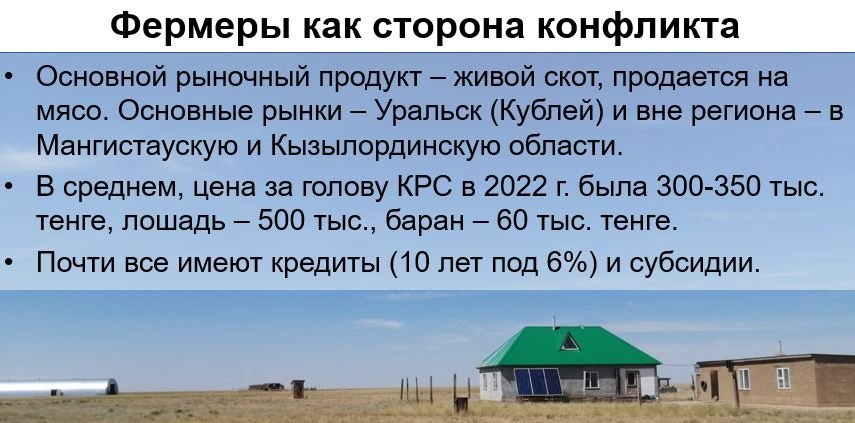

ACBK researcher Ilya Smelyansky outlined the region’s agricultural landscape. Most farmers engage in livestock breeding, with little crop farming aside from fodder production. The average farm (1-3 people) covers about 500 hectares, but larger operations (more than 10 people) can span up to 9,000 hectares.

Farmers typically lease land for 10 to 49 years, with a wintering site (point), one or three jailau (seasonal pastures), + a house in the village.

They usually keep one or two types of livestock, which include cattle (250–300 head per farm usually, up to 1000), horses (30–350), and sheep/goats (400–1,000).

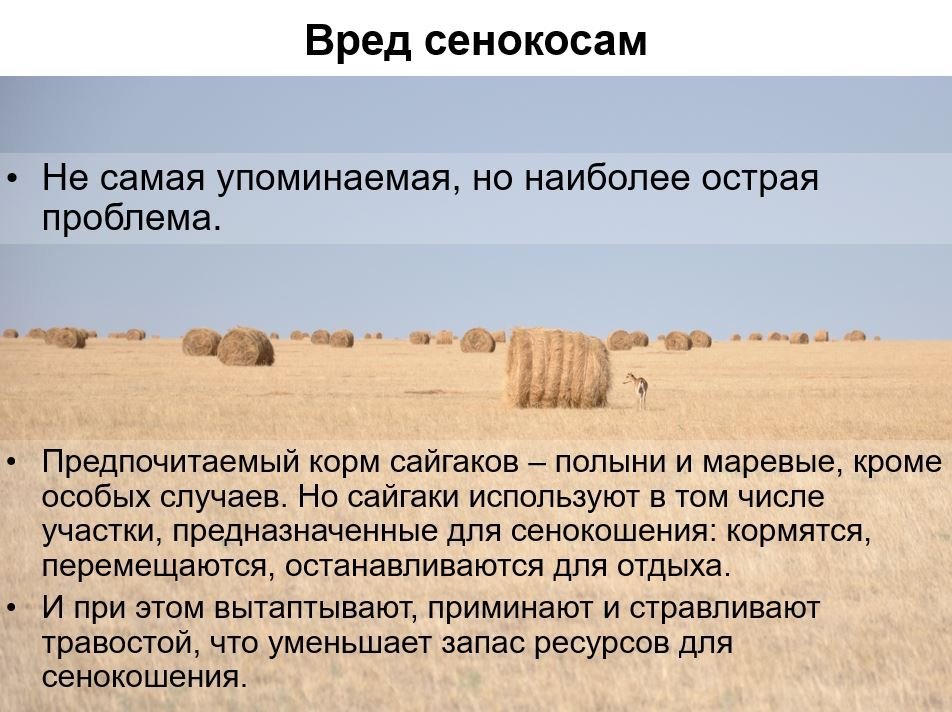

Hay is crucial for livestock survival during the harsh winters (two to four months), and the shortage of hay and hayfields is the most threatening problem.

A typical farmer requires around 550 tons of hay (2,200 rolls of 200–300 kg) each year, requiring 1700–2000 hectares of land for harvesting. However, hayfields are scarce; farmers often mow wherever possible, even in pastures. During droughts, they even rely on floodplains and estuaries.

There is a local hay market operating within districts and even at the village level.

During droughts, hay is imported from other regions, including the Aqtobe region. In 2022, the price of a 250 kg roll ranged from 3,500 to 7,000 tenge, with an average of 6,000 tenge, reaching 10,000 tenge during drought.

Water levels heavily influence hay availability in low-lying areas such as estuaries.

The conflict between farmers and saigas dates back to the late 1990s when both populations were much smaller. As farmland expanded, it encroached on the saiga’s traditional range. When saiga numbers rebounded, they returned to find their habitat occupied by farmers.

Data presented by Aibat Muzbay from the Eco-Museum illustrates the rapid expansion of both saiga populations and farmland:

- 2000: 17,500 saigas, 22,939 hectares leased to farmers

- 2010: 39,000 saigas, 60,763 hectares leased

- 2015: 51,700 saigas, 210,740 hectares leased

- 2020: 217,000 saigas, 460,079 hectares leased

- 2023: 1,130,000 saigas, 557,667 hectares leased (53%)

With the agricultural sector reaching unprecedented levels, the saigas are now seen as an obstacle to further expansion.

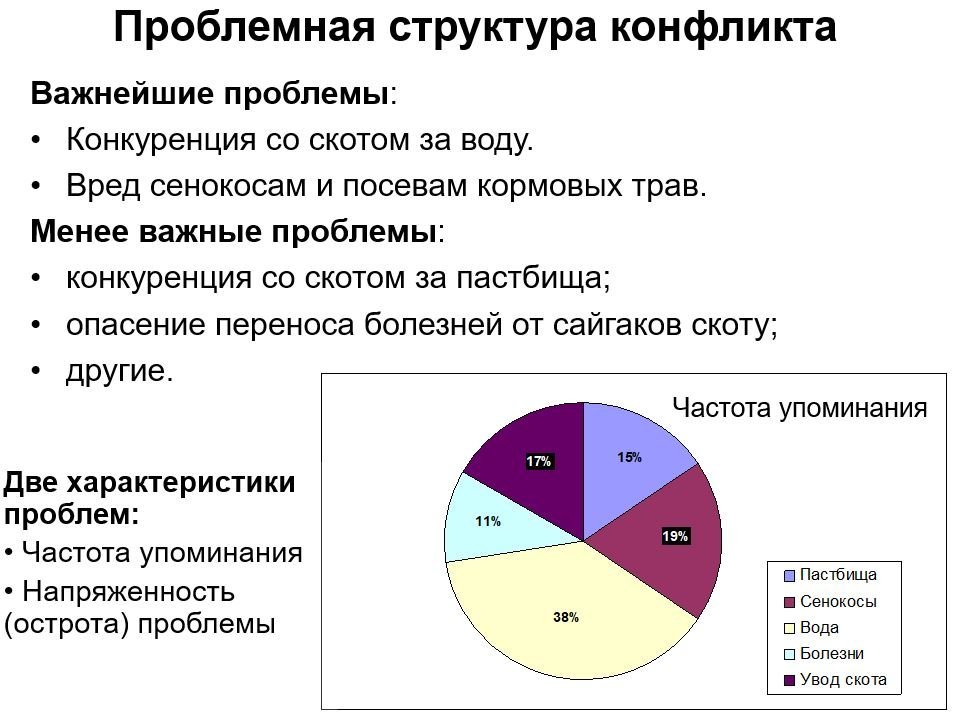

According to surveys conducted by ACBK, around 70% of farmers believe saigas cause damage to their operations. Roughly 65% rank saigas among their top three farming challenges.

Between 2016 and 2020, the saiga population exceeded 200,000.

Farmers reported various issues, including:

- Saigas trample hayfields, dig holes that disrupt equipment

- Eat grass, reducing available fodder for livestock

- Scatter and trample mown windrows, making hay collection more difficult

- Contaminate hay with excrement

- Die in fields, with their unremoved carcasses obstructing haymaking equipment and spoiling the hay

-

Water shortages: Saigas consume limited water supplies, forcing farmers to spend more on water extraction and sometimes pushing livestock away from watering holes.

- Pasture degradation: Competition for grazing land leads to overuse and displacement of livestock

- Fear of disease transmission: While no confirmed outbreaks have been linked to saigas, farmers worry about potential risks, especially given the presence of dead saigas in the steppe

- Infrastructure damage: Saigas break electric fences, leading to additional costs

- Traffic accidents: Though rare, collisions between saigas and vehicles on highways pose risks

- According to respondents, the penalties for poaching—especially for non-harmful but legally prohibited activities like collecting saiga horns and other derivatives—are excessively harsh

About 25% of those who reported damage did not estimate their losses, even approximately. Among the 61% who provided a quantitative estimate, most measured their losses in unharvested hay bales, ranging from several hundred to 5,000–6,000 large bales (250–300 kg each). The most common estimate was around 550 bales.

Less frequently, damage was measured in terms of the size of affected hayfields (ranging from 100 to 1,700 hectares), the weight of unharvested hay, or financial losses, which were estimated at 5–10 million tenge per year.

For many farms, losses averaged around 3.3 million tenge, but due to very large farms, the total damage — when distributed across all farms — amounted to approximately 10 million tenge.

Damage to forage crops was assessed similarly. While the affected areas were smaller, the financial impact per unit of land was greater due to higher yields. In addition to lost profits, farmers also faced direct investment losses, including expenses for seeds, agricultural treatments, and irrigation.

In one example, a respondent reported losing 20% of a 200-hectare Sudan grass field, resulting in investment losses of 1.8 million tenge and lost profits from hay sales totaling 3 million tenge, bringing the total loss to 4.8 million tenge.

Respondents did not provide specific estimates for damages related to watering places and pastures. Additionally, government agencies and other organizations did not conduct a proper quantitative assessment of these losses until 2024.

The peak of the conflict coincides with the saigas’ annual migration to lambing grounds in April-May, a time when livestock are also moved to summer pastures.

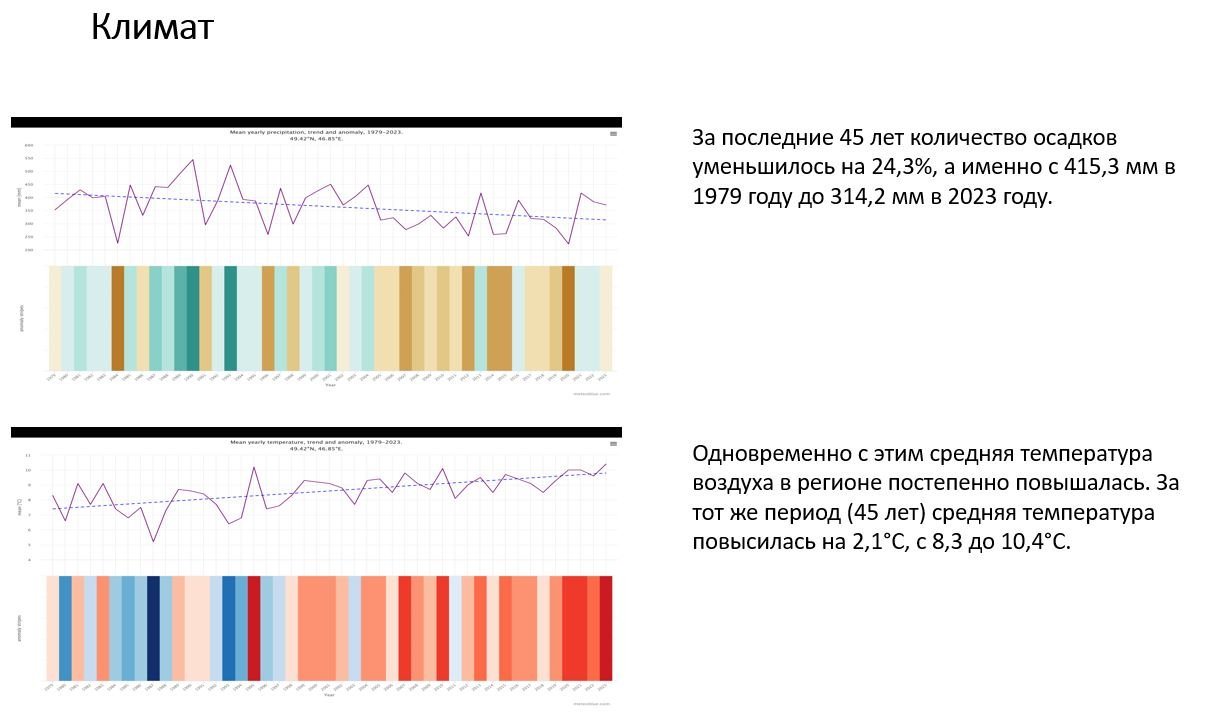

Climate conditions further exacerbate tensions, with droughts intensifying the struggle for resources.

The intensity of the conflict varies across the region, with some areas experiencing heightened tensions while others remain relatively unaffected. A key factor influencing this distribution is the availability and type of water sources. Additionally, livestock density and grazing pressure play a significant role in shaping the conflict dynamics.

Most respondents expressed a measured hostility toward saigas. While some acknowledge their ecological importance and role in nature, they remain uninterested in their broader impact and believe the population should be significantly reduced or relocated away from their lands. They see no direct benefits from the presence of saigas.

A smaller but vocal group — around 20% of respondents — holds a more extreme view, believing that saigas no longer have a place in the region and should be exterminated.

In contrast, approximately 15% of respondents recognize the ecological value of saigas, considering them beneficial for steppe ecosystems and valuable and aesthetically essential animals.

Local farmers see reducing the Ural saiga population as the only viable solution to the conflict. Those in the northern part of the region believe the optimal saiga population should be 100,000 to 150,000, while farmers in the southern part are more tolerant, suggesting they could coexist with 300,000 to 500,000.

At the same time, some farmers are willing to tolerate saigas on their land — but only if they receive full compensation for the economic losses caused by the animals.

Conference participants also highlighted another major challenge for farmers: climate change.

Increasingly frequent droughts, sharp temperature fluctuations, and other extreme weather conditions are affecting water availability and food supply.

Many farmers do not acknowledge climate change as a key factor and instead attribute all issues related to drying reservoirs and declining pastureland solely to the growing saiga population.

Finding solutions to the conflict was not the main focus of the conference, so speakers rarely proposed specific measures.

General principles and approaches to resolving the issue are outlined in the Strategy for the Conservation of Saiga and Management of Its Populations in Kazakhstan, which was developed two years ago with input from leading global experts.

When asked how the situation could be addressed, conference participants agreed there is no simple or perfect solution to such a complex issue.

Several potential approaches were suggested:

- Managing saiga population growth, potentially through controlled hunting, with a portion of the revenue benefiting local communities

- Regulating livestock expansion to reduce competition for resources

- Improving water access by flooding pastures and creating additional watering points for both saigas and livestock to minimize conflicts over water

- Compensating farmers for verifiable economic losses caused by saigas

- Fencing off critical hayfields and forage crops to protect them from saiga activity

- Mandatory livestock vaccination to prevent the spread of diseases between saigas and domestic animals.

- Stricter grazing regulations in protected natural areas to preserve ecosystems

- Ongoing monitoring of the saiga population, its interactions with livestock, and its impact on pastureland

Original Author: Danil Utyupin

Latest news

- Modernization of Syrym Checkpoint Promises Smoother Border Crossings—but Not Without Challenges

- Foreign Minister Nurtleu Represents Kazakhstan at BRICS Summit

- Russia Approves Duty-Free Oil Supplies to Kazakhstan Through 2028

- Trump Sends Tariff Warning Letters to Global Leaders, Including Over Kazakh Imports

- Russia’s Transport Minister Roman Starovoit Dies by Suicide After Resignation

- Almaty Celebrates National Dombra Day

- Trump Threatens 10% Tariff on Countries Supporting BRICS Policies

- Why Did Kazakhstan’s President Not Attend the Azerbaijan Summit?

- Beijing Celebrates Dombra Day with Kazakh Music Performance

- Kozhamzharov’s Circle: What Are Investigators Hoping to Find?

- “I Want to Be Nazarbayev”: How Academician Yespolov’s Grandson Joined the Elbasy Clan

- Armenia Denies Russian Military Reinforcement at Gyumri

- Mayors Detained in Türkiye as Part of Fraud Investigation

- Olesya Keksel Reportedly Involved in Criminal Case Over BTA Bank Torture Allegations

- Mother of Conscript Claims Son Was Committed to Psychiatric Institution Without Consent

- President Toqayev Sends Nazarbayev Birthday Wishes

- Toqayev Appoints New Ambassadors in Series of Diplomatic Changes

- Unidentified Object Resembling Drone Found in Atyrau Region

- Trump and Zelenskyy Discuss Air Defense Needs

- Rapper Qurt: Wife Withdraws Statement in Court