Elusive Oil: Kazakhstan VS Kashagan Investors

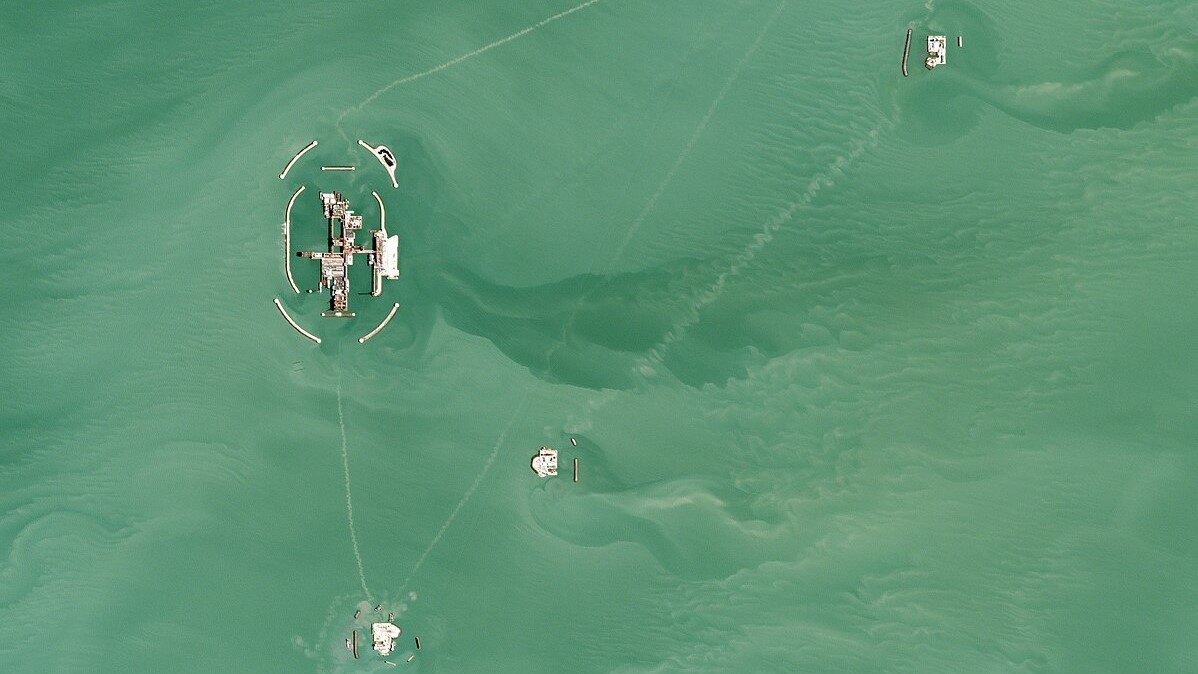

Kashagan. Photo: Psa.kz

Kashagan. Photo: Psa.kz

The Kazakh word "Kashagan" is roughly translated as “elusive.” The field's name somewhat predicted the outcome: record investments were made, yet their economic return leaves much to be desired. Orda.kz has looked into how this became protracted litigation between Kazakh authorities and foreign investors.

In April, reports surfaced that the Kazakh authorities had upped the claim amount against the developers of the Kashagan oil field to $150 billion. They are seeking compensation for lost profits. Authorities initially anticipated recovering $15 billion from the NCOC consortium, the Kashagan operator. They would later tack on the loss of earnings from the potential sale of oil, which investors promised.

It Just Keeps Going and Going...

Kazakhstan and optimistic foreign investors expected quick profits. Contract redrawing became the authorities' and NCOC's constant activity, however. International arbitration would later come to the fore.

In 1997, the Kashagan development project was seemingly set up for success. Before its launch, there was evidence of oil in this area. The field would occasionally release oil, and large oil seeps were often found in its area. When the first exploratory well was drilled in 1999, hopes for big profits were high. It was impossible to foresee future troubles.

No one could have assessed all the risks. The composition of the oil with a high content of hydrogen sulfide turned out to be a big unpleasant surprise. I remember the words of the consortium's first CEO, Keith Dullard of Shell. While everyone was euphoric after discovering the 15th unique field in the world regarding oil and gas reserves and hope for the “Kuwaitization” of Kazakhstan, he did not share this optimism at all. I remember word for word what he said: if half of the costs go to solving the issue of gas and hydrogen sulfide utilization, then the project is doomed to be unprofitable, recalls oil industry analyst Artur Shakhnazaryan.

Under the contract terms, investors were given four years to explore the field, two years to evaluate reserves, and another four years for pilot development. Expecting the first oil just four years after exploration and evaluation was questionable. The longer the development of Kashagan progressed, the clearer it became that it was impossible to get the first oil by 2008.

Immediately after Kashagan's opening, when it became clear that the composition of the oil, geological conditions, and logistics were utterly different, the contract had to be rewritten to suit the emerging circumstances. But no one bothered to mention it. Politics 'outplayed' the real economics of the project, and the economics of the project is a given that cannot be deceived. Kashagan was doomed to be problematic from the start, says Arthur Shakhnazaryan.

The first broken promise to start oil production at Kashagan was in 2008. The dispute was then resolved by signing an additional agreement. Its terms stipulated that the consortium would make concessions to postpone the deadline for the first oil production from 2008 to 2013. KMG's share in the project was increased from 8.33% to 16.81%. Meanwhile, the government of Kazakhstan reserved the right not to recognize the consortium's expenses as reimbursable costs if commercial oil production did not begin before October 1, 2013.

The Kashagan development project has been delayed, both in terms of time and budget. Its operating model has changed several times. Ultimately, they came to the conclusion that all shareholders in the form of a consortium approved a single operator and are now working according to this model. Previously, one shareholder was responsible for drilling, another for offshore projects, a third for onshore projects, a fourth for social projects, and so on. With this arrangement, it was very difficult to control costs. In 2008, changes were made to the PSA - the cost of the project's first phase was increased. Then Kazakhstan also introduced a royalty, which depends on world oil prices. The operators pledged to produce oil by 2011; otherwise, they would voluntarily pay fines,explains Nurlan Zhumagulov, director of the public fund Energy Monitor.

In 2013, production came close to launching. But the joy was short-lived: after a couple of months, the pipe through which gas flowed cracked due to the high hydrogen sulfide content. The consortium had to rebuild the pipeline. And the costs of 2013-2016 no longer had to be reimbursed by future oil revenues.

The lion’s share of the amount of claims falls precisely within this period of time - from 2013 to 2015. The government of the Republic of Kazakhstan has not recognized all expenses of the consortium as investments. Another part of the unrecognized amounts arose due to the activities of the supervising structure, PSA LLP. A number of tenders conducted by the consortium were declared invalid by PSA LLP. The position of foreign investors is “non-recognition of the right to non-recognition.” The expenses were actually incurred, and according to the terms of the contract, they should be eligible for reimbursement, says Arthur Shakhnazaryan.

Treacherous Hydrogen Sulfide and Broken Promises

The delay in starting production is why Kazakhstan demands the eye-watering $138 billion from NCOC. The authorities believe that since they did not receive the promised oil on time, they have the right not to recognize investors' expenses. The original contract does not contain provisions regarding the government's recognition or non-recognition of costs. Arbitration in Geneva will most likely be based on the original agreement.

There are world-famous investors in Kashagan - Shell, Exxon Mobil, Inpex. But they faced harsh conditions in Kazakhstan. The Caspian Sea freezes in winter. The Kashagan field has a high hydrogen sulfide content - about 18%, and high reservoir pressure. And all this needs to be extracted at sea, transported through an oil pipeline to land, and exported through Russia to the CPC sea terminal. All this entails huge costs. A little later, the shareholders were faced with the fact that the Caspian Sea was becoming shallow - they carried out dredging work for hundreds of millions of dollars and began to buy hovercraft. But these ships are very noisy. Many environmentalists believe that they negatively affect the flora and fauna of the Caspian Sea and oppose their use. It’s hard to blame the shareholders, but costs have increased, and Kazakhstan is also right here: we never got the 'big oil',Nurlan Zhumagulov says.

Kazakhstan has reasonable grounds for its claims. President Qasym-Jomart Toqayev has repeatedly instructed the shareholders to present a plan for Kasgagan's full-scale development. But the shareholders never did. They assured they would build a 2 billion cubic meters gas processing plant but failed to follow through.

Kazakhstan, therefore, decided to create this enterprise. Now, the authorities are negotiating with potential investors from Qatar. The estimated capacity has increased to 2.5 billion cubic meters. Who will build the plant remains a point of contention. Investors can still return to the project, and time is not in Kazakhstan’s favor.

Summing up the interim results of the investors’ work at Kashagan, we can say that they could have done everything better - but it’s too late. The field has been developed for more than 20 years. Now we need to look forward: what we spent, we spent, but will they be able to recoup this investment? says Abzal Narymbetov, business analyst.

Arthur Shakhnazaryan believes that Kazakhstan’s chances of winning arbitration against NCOC are quite modest.

The authorities' position regarding the first category of claims related to violations of the deadlines for starting oil production looks unconvincing. There is a slightly higher probability of proving violations on the part of the consortium during tenders.

If there are truly gross violations of tender procedures, and the consortium did not correct them, despite the claims made, then there are some chances for lawyers from the Republic of Kazakhstan in the Geneva Arbitration, Arthur Shakhnazaryan believes.

Legal Nonsense

Arthur Shakhnazaryan points out that the government is going to court with its national company. KazMunayGas is also a shareholder and is part of a consortium.

This is legal nonsense. In essence, Kazakhstan is suing itself. Actually, this is why PSA LLP was removed from the national company KMG in recent years and equated as a separate structure to the Ministry of Energy of the Republic of Kazakhstan. We corrected the legal contradiction for arbitration, but it turned out even worse. Now PSA LLP is an incomprehensible structure, not specified in the terms of the project , says Arthur Shakhnazaryan.

Abzal Narymbetov is also unsure of Kazakhstan’s chances of receiving the $150 billion.

According to him, the lawsuit between NCOC and the authorities will unlikely lead to foreign investors backing out. They have invested too much money to simply leave the project without even a hint of profit.

It is also unlikely that the state’s share in the project will increase, as in 2010 at Karachaganak. Such an attempt would lead to a legal response and endless litigation. Kazakhstan has yet to win major lawsuits with foreign companies. Reputation damage has occurred, however, as in the sluggish “Stati case.”

Nurlan Zhumagulov is more optimistic. He believes that Kazakhstan could win the arbitration proceedings over Kashagan. He hesitates to estimate the amount of lost profits the country can reimburse.

In fact, our situation in Kashagan is more or less good. The arbitration always listens to both sides, finds some kind of happy medium - and this happy medium, in my opinion, will still be closer to Kazakhstan’s position on the Kashagan project. Theoretically, 70 to 30%. This is a normal process, especially since we are talking about non-reimbursable costs that cover the period from 2010 to 2019, and there are still non-reimbursable costs from 2019, notes Nurlan Zhumagulov .

Currently, Kashagan produces about 400 thousand barrels of oil per day. Production is complicated by natural conditions, technical problems, and numerous complications. NCOC investors, led by the Italian Eni, still believe this figure can be increased to 1.5 million barrels daily.

During Kashagan's operation, the field produced 105 million tons of oil, worth about 65 billion dollars. This is half the amount that Kazakhstan is currently demanding from NCOC.

Another Kashagan?

Another long-term oil project is the “future expansion project” (FEP) in Tengiz, which Chevron plans to implement. In March, reports emerged that its cost would reach $48.5 billion.

The full-scale launch of the Tengizchevroil expansion project, known as the future expansion project, has been postponed until the second quarter of next year. The project has gone well over its original $37 billion budget, and its expected completion date, originally set for mid-2022, has already been pushed back twice. Bloomberg reported.

According to Nurlan Zhumagulov, the Tengiz FEP is the most capital-intensive in the world. Its budget is $47-48 billion. It should increase oil production in Kazakhstan by 12 million tons per year.

The project also involves creating a facility to pump raw gas back into the formations to maintain the pressure, which drops annually.

The expert points out that the project should positively affect Kazakhstan's budget. Tengizchevroil's taxes should double. KazMunayGas's profit, which has a 20% share in the project, will also increase. Nurlan Zhumagulov is confident that the FEP should increase Kazakhstan’s GDP by about 2% in the future.

Whether the FEP at Tengiz will become a “second Kashagan” is worth considering.

The Tengiz Future Expansion Project is not a dead-end project. It seems that investors did not expect it to be so costly and long. There are reasons for this, related to logistics, management, and investors themselves are interested in spending more - this will allow them to recoup more money later, and Kazakhstan will get less. The more costs investors have, the worse it is for Kazakhstan, summarizes Abzal Narymbetov.

Run, Investor, Run

According to industry experts, negotiations on the possible transfer of rights to develop Kazakhstani fields to new investors are not currently underway. None of the foreign companies have announced their withdrawal from oil investment projects in Kazakhstan. When the licenses of existing investors expire, KazMunayGas will be able to benefit from oil production being prioritized. But not anytime soon.

The contract for developing the Tengiz field expires in 2033, and negotiations on its extension will begin in 2028. The license for developing the Karachaganak field is valid until 2037, and Kashagan—until 2041. There is indeed enough time to reach a consensus.

The contract under the terms of the production sharing agreement (PSA) for the North Caspian project expires in 2041. So foreign investors still have 17 years until their licenses expire. And in the “Concept of Full Development of the Kashagan Field” adopted by NCOC, the timing of the fourth expansion of production is scheduled until 2054. This stage of the project involves the construction of a fourth oil and gas treatment plant (so far there is only one such installation), says Arthur Shakhnazaryan.

However, since questions regarding the project's first stage have yet to be resolved, the consortium has no reason to engage in the next ones, including building a second-generation plant.

The project is very complex. Shareholders still cannot decide to implement the second phase of Kashagan because total investments have already exceeded $60 billion. If they contribute the same amount of money to this project, and their contract ends in 2041, it is not a fact that they will be able to recoup the investment, points out Nurlan Zhumagulov .

According to Arthur Shakhnazaryan, Astana is tired of dealing with a conglomerate of international oil corporations that cannot consistently carry out a single development and sometimes contradict each other.

He says that by putting pressure on NCOC, authorities expect to play on internal disagreements.

There were contradictions between the consortium members from the very beginning. For example, when choosing a location for a second oil and gas treatment plant, Shell and Exxon Mobil chose Tengiz, while Eni and Total wanted to build it near the first one - Karabatan, near the village of Western Yeskene. With controllability in the project, everything is quite complicated. Now, there are seven participants, and each of them has the right to veto every project decision, which creates great difficulties. Arthur Shakhnazaryan

According to experts, NCOC participants' costs will be compensated closer to 2036 if production volumes are maintained. This means the consortium will have less than six years to profit. Expanding the project further translates into maintaining high rewards for investors.

Kashagan is already the most expensive project in the oil industry's history. It will be extremely difficult to find such investors with long-term finances and the necessary technologies. Project participants should not sort things out in arbitration but enter into complex negotiations. It would make more sense. But since it is diamond against diamond, only one will break. summarizes Arthur Shakhnazaryan.

Original Author: Nikita Drobny

DISCLAIMER: This is a translated piece. The text has been modified, the content is the same. Please refer to the original article in Russian for accuracy.

Latest news

- Aqtobe Region: Life Sentence Issued in Double Homicide and Hostage Case

- Karakalpak Court Upholds Sentence Against Activist Extradited from Kazakhstan

- Former Qazseleqorgau Officials Sentenced in Corruption Case

- Deputy Commander-in-Chief of the Russian Navy Reportedly Dies in Kursk Region

- Toqayev Sets Priorities for New Transport Minister

- Armenian Parliament Advances Bill to Nationalize Electric Networks of Armenia

- Appeal Withdrawn in Alina Serikova Case, Sentences Remain Unchanged

- Toqayev and Nazarbayev Congratulate Lukashenko on Belarus Independence Day

- Armenia: Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Reaffirms Commitment to South Caucasus Connectivity Initiative, Recalls 'Crossroads of Peace'

- SK-Pharmacy Undergoes Management Shakeup Amid Scrutiny

- Supporting Farmers and Boosting the Economy: Bektenov Reports to Toqayev on Government Progress

- Final Ruling: Court Dissolves Perizat Kairat’s Charity Foundation

- From Station Cashier to KTZ Chair: Who Now Runs Kazakhstan’s Rail Sector

- Kazakhstan to Restrict Loans for Conscripts

- Details Emerge in Corruption Case Involving Former Vice Ministers and Credit Bureau Head

- Former Armenian President Serzh Sargsyan Faces Corruption Charges

- Tensions Persist as Azerbaijan Presses Russia on AZAL Investigation

- "Off Course": Exclusive Photographic Evidence and Analysis of Drones That Crashed in Kazakhstan

- Kazakhstan Temir Joly in Debt — But Posts a Profit. How Did That Happen?

- North Kazakhstan to Use 45 Billion Tenge from Returned Assets for Water Projects