Water Access Issues Spark Debate in Aqshi Village

Photo: Orda.kz

Photo: Orda.kz

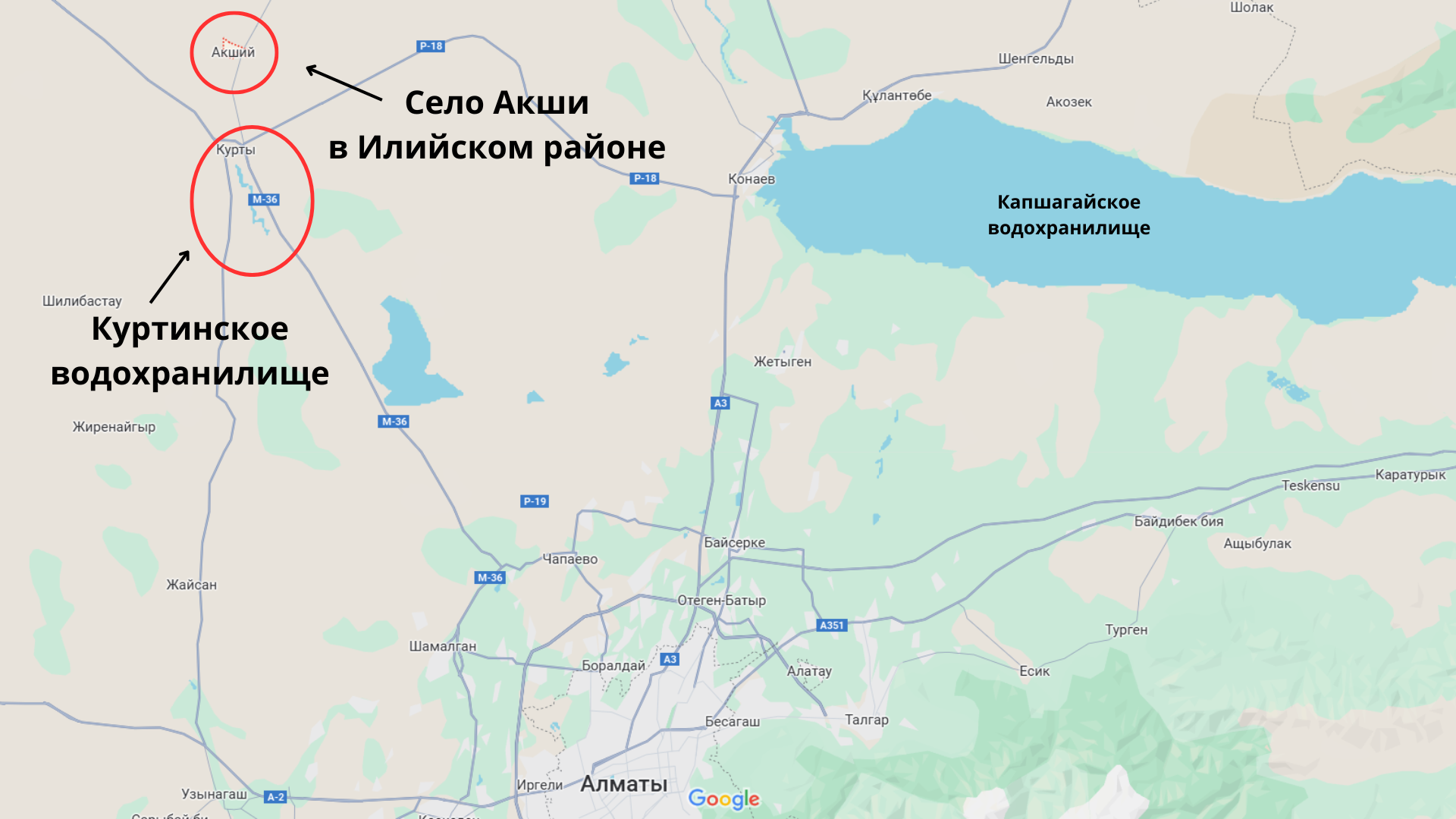

The agricultural season in Aqshi village, located in the Ile district of Almaty region, started earlier than usual this year thanks to an unusually warm spring—a reason, it seemed, to celebrate. But by May, optimism gave way to crisis: temperatures soared to 45°C, and not a single drop of irrigation water was available.

When an Orda.kz journalist visited the village to report on the sowing season, she found herself in the middle of a dispute. Dozens of farmers gathered outside the local Akimat building to demand water, pointing to dry, empty irrigation ditches. And by the end of the day, it became clear that the entire situation could have been resolved in just one day.

Despite the nearby Kurty reservoir being full, the canals remained dry. Farmers who had rushed to plant alfalfa, vegetables, and melons now saw their early sprouts shriveling under the brutal sun.

This man planted watermelons — he’s done, the field is burned. But he invested money, and now the land needs to be plowed, processed, and seeded again. All our seeds are imported and expensive, we don’t have our own. It’s all money, and in the end we get the short end. Same thing happened last year—but at least we got water a little earlier then. This year, even the canals aren’t ready,said farmer Igor Schmidt.

On The Brink

Aqshi is home to about 5,500 people. It has two schools, a sports complex, a House of Culture, and even an award-winning village library.

While there are about 270 registered livestock breeders, only around 100 are active. Crop farming is in decline, with only 97 crop growers remaining, and just half of them still working their land.

So when farmers and livestock breeders gathered at the Akimat that morning, they all shared the same frustration: the Kurty reservoir, just 10 kilometers away, was full, but no water was being released.

The water and a storage tank are there. Water was given on time all our lives. But there have been delays for the last three or four years. We have vegetable gardens and planted seedlings, but they do not give us water. And why do they do that? The irrigation system isn’t ready. But why isn’t it ready? That’s not our problem. The entire Ministry of Water Management was opened two years ago. And here, water only gets more expensive every year, said Igor.

As the temperature soared past 40°C, the fields cracked with dryness, and people boiled over with frustration. For many, it meant losing their entire investment — and their harvest.

“We’re Farming on Credit"

Igor Schmidt, a local cattle breeder, explained the financial risks farmers take each season. On paper, farming might look simple—tractors, fields, harvests. In reality, it's a daily grind against weather, debt, bureaucracy, and a lack of accountability.

In early spring, we begin plowing, preparing the soil, and planting. Then the irrigation ditches are stretched and the land is watered, which should have happened from the beginning of May, but it didn't. The alfalfa we planted in April grew 5–10 cm. Now, it’s all burned.he said.

This season, Igor invested again: two tractors on credit through KazAgroFinance, imported seeds, and extensive field prep. One hectare costs at least 200,000 tenge, and he planted five. All of it depends on irrigation — without water, the investment is lost.

If they had given us water at the beginning of May — like they used to — we would’ve finished the first irrigation by May 10, and everything would’ve been fine. But now we’ve lost another 20–30 days. And then by the time we mow, harvest, deal with plant stress, and wait for the second growth, we’re already behind. We manage a second cut, but don't make a third one. In August, they shut the water off again. If everything was done on time, we’d get three, even four cuts, with the last one around late August or early September. The whole cycle needs about a month and a half.Igor lists.

Farmers in Aqshi mainly grow alfalfa, watermelons, cucumbers, tomatoes, and potatoes. Those with larger plots store food for their own livestock and sell the surplus locally or at Altyn Orda market in Almaty.

But even that modest trade depends on reliable irrigation, and without it, they can’t even pay their machine operators, who earn around 150,000 tenge per month, often paid in cash or hay.

On average, we get 150 bales of hay per hectare per mowing. One bale sells for around 1,000 tenge, so that’s 150,000 tenge in profit—from just one cut. We usually get three mowings per season; a fourth is rare. But now, with this water shortage, the first cut is already lost. Everything’s scorched. Just look at this heat — no rain, no water,a farmer explains.

What makes the situation even more frustrating is that the villages of Aqshi and Kurty are located right next to the Kurty reservoir. Yet, water still doesn’t reach their irrigation ditches.

"The land costs nine million, seven million for maintaining, plus 800,000 for seeds. And in the end, millions into the air!" says farmer Saparbay.

The Akim Who Wasn’t Afraid

Amid a crowd of frustrated farmers, one figure stood out — a young man in a crisp white shirt and trousers. It was Dulat Abilgani, the acting akim of the Kurty rural district. While many officials tend to avoid journalists, Dulat did the opposite: he approached them, shook their hands, invited them to his office, and spoke openly about the situation.

They say there's little water and no reserves. But I went there myself — there's plenty. They’re dumping water into the river, claiming it’s dangerous to store more. Last year they conducted an assessment—there’s no risk. Apparently, they just don’t want to do their job,he said.

Officials from the Big Almaty Canal (BAC) named after D.A. Konayev gave a range of explanations: safety risks, missing contracts, and ultimately, unpaid debts by water users.

I’ve sent letters everywhere — to the prosecutor’s office, the National Security Committee, and BAC. Their position is that the akim should collect money from debtors. I ask them: 'Have you at least given notices to these debtors?' They say, 'You should give them out.' I offered them an office (in the Akimat building - Ed.) so that they could collect payments and sign contracts. I am not authorized to collect money - there is a corruption risk. For example, who collects gas payments? The representatives themselves. So do electricity providers. I told them, ‘Assign someone, let them handle payments here.’ But they don't want to, Dulat said.

Dulat doesn’t speak like a bureaucrat — he speaks like someone who genuinely cares. He doesn’t even need the water himself; he has no farm. But he fights for his community, and that deeply impressed the visiting journalist.

Later that day, BAC representative Abzal Rakhimbayev arrived in the village, only to be met by an angry crowd:

– “We provide water, but none of you have paid in two years!” he claimed.

– “Who didn’t pay? Name names!” someone shouted.

– “Everyone who took irrigation water owes money.”

– “Show us the contracts! Ours don’t even have dates!”

– “Payments go through one person or through the Akimat — what are we supposed to do?”

– “Are you above the people?! There’s nothing to water the livestock with. Everything’s dying. And your solution is to carry water in buckets? Is that your official position?”

In response to mounting pressure, Rakhimbayev promised water would be released that day, starting with canal flushing. The farmers agreed to wait and invited the journalist to join them for a bowl of shubat.

Hospitality Runs Deep

Among the villagers was Jambyl aga, a local aksakal and proud owner of 60 camels. Known for his warm hospitality, he insists on treating visitors to shubat, a traditional fermented camel milk drink. He and his wife moved to Aqshi with just two camels; now, their growing herd supplies milk to both locals and customers in the city.

I am 71 years old, thanks to Shubat, I look and feel good. Camel meat is also healthy — it has no cholesterol. The hump is used to treat hemorrhoids — you need to eat it every day, and it goes away. People with cancer come here from Almaty and Shymkent for fresh milk straight from the camel,Jambyl aga says, offering a bowl.

In between conversations, local mobile videographer Serik quietly remarked that the canal flushing likely hadn’t even begun. He suspected the announcement at the meeting was just for show, meant to create the impression that the issue was resolved, hoping the journalist would leave thinking the problem had been taken care of.

Determined to get the truth, the journalist joined acting Akim Dulat Abilgani and local farmers to inspect the reservoir firsthand.

Dry Promises

The Kurty Reservoir, in use since 1967, provides irrigation water to both the Ile and Jambyl districts. In Soviet times, vegetable storage facilities lined its banks — now abandoned.

As they approached, Dulat explained that when water is released, it creates a distinct sound — a rush that everyone recognizes. But on this day, there was only silence.

Abzal Rakhimbaev's words turned out to be empty promises. The channels remained dry, and there was no water pressure at the dam. A visible line along the reservoir wall confirmed the low water level.

They then headed to the nearby fields, including those owned by farmer Saparbay, where there wasn’t even a hint of irrigation. His crops, like many others, had withered.

Disappointed but determined, the group returned to the village, waiting now for the BAC Deputy Director, Samat Yensegen, to explain what would happen next.

So Who’s to Blame?

By evening, Samat Yensegen arrived. His presence reignited debate among villagers and officials alike.

You think just turning on the water solves everything? But the problem will remain anyway. We face it every year. It’s just that now the media has gotten involved — at least something has moved. Let’s be honest— who always gets blamed? BAC. The one with the water is always to blame,he said.

Yensegen acknowledged that the system is broken. There’s no clear process for working with farmers — no direct contracts, proper prepayment system, or structured communication. Everything is handled informally, often with verbal agreements and bureaucratic roadblocks at every step.

I would also like it to be like with an electricity meter, just turn it on and pay as you go. But we don’t have a law like that. Drinking water is metered, but when it comes to irrigation, everything is handled verbally and through intermediaries. And what happens if someone’s paperwork isn’t in order? One person submits everything, the other doesn’t— and the first ends up suffering for it. No one files formal complaints; everyone just talks.

In the House of Culture, villagers pushed back. Why should the entire village be punished because some haven’t filed documents?

You say, ‘Give it only to me and my neighbor.’ But our contracts don’t have provision for selective distribution. Sure, you don’t owe anything. But 46 others do. How do we work around that?said a water utility representative.

Another core problem: payment collection. BAC isn’t legally allowed to accept cash — no cash register, no receipt, no legality. But the Akimat can’t collect payments either, due to corruption risks. The result? A financial no-man’s land where responsibility is passed around without resolution.

The farmer only knows his rights. Who will remember his responsibilities? Everyone wants water — some want it for free. Then they start shouting.

And they did. Farmers stood up and demanded answers: Where are the contracts? Where are the names, the amounts, the paperwork? To which they receive in response:

The First Drop

After nearly two hours of heated discussion, a decision was made: water would be released today. When villagers and the journalist returned to the canal, they finally saw a stream flowing through. For now, it was only a flush, but by morning, the long-awaited irrigation would begin.

If you hadn’t come, nothing would’ve happened. Your involvement helped resolve this. Did you see anyone show up this morning? No. This issue had to be raisedsaid Dulat Abilgani, acting akim of the Kurty rural district.

Samat Yensegen added gravely:

Don't let this issue go. This concerns not only farmers. This is our common problem - no one wants to work proactively. Everyone wakes up when it's already scorching hot at 45 degrees.

Water wasn’t released because the system worked — it was released because villagers protested, and the issue reached the media. In Kazakhstan, farmers don’t get irrigation by contract or by schedule—they get it by how loud they shout.

It’s a vicious cycle: One person doesn’t pay, and everyone loses water. Contracts are signed, but lack dates.

Canals sit dry because no one knows who’s supposed to prepare them. Responsibility is spread across agencies, yet somehow lands nowhere.

What farmers really need is a working system: a clear schedule, formal contracts, direct communication, and minimal red tape. A structure that functions before crops wither, not after tempers boil over.

Otherwise, the villagers may be doing much of the same come next May. The people of Aqshi are not ones to give up easily, though.

Orda.kz has submitted formal inquiries to the relevant departments to help identify how this broken system can be fixed.

Original Author: Alina Pak

Latest news

- Citizen of Kazakhstan Fined in Russia After Forcing Anti-War Message on St. Petersburg Radio

- Criminal Case Opened Against KazTAG Leadership

- East Kazakhstan Transport Department Head Resigns Amid Corruption Probe After Bridge Collapse

- Toqayev Meets EEC Chair Sagintayev Ahead of Upcoming Eurasian Summit

- Apple and Google Warn of State-Backed Cyberattacks Targeting Users in 150+ Countries

- Kazakhstan: FMA Uncovers Illegal Online Casino Scheme

- Kazakhstan Exporters Sound Alarm as KTZ Imposes Over 20 Rail Transport Bans

- Lawyer: House Arrest Prevents Orda.kz Head Bazhkenova from Defending Herself in Court

- KTZ, Uzbekistan Railways Expand Grain Transit Amid Border Congestion

- Shymkent Military Court Sentences Fuel Depot Chief to Nine Years in Prison

- Let’s Install a Thousand Towers! How Environmentalists Propose to Clean Almaty’s Air

- Armenia Releases Former “Golos” Coordinator Wanted Under Russia’s Foreign-Agent Law

- Kadyrov Calls Russian Strikes “Response” to Grozny City Complex; MoD Makes No Direct Mention

- Kazakhstan Seeks Solutions to Ease Pressure on Uzbek Terminals Amid Export Surge

- Georgia’s Security Service Says No Evidence of “Kamit” After BBC Report

- Kadyrov Confirms Drone Damage to Grozny City

- Russia Temporarily Blocks Kazakhstan's Grain Transit, Threatening Flax Exports to Europe

- Assets of Businessman Dulat Kozhamzharov Seized Following Halyk Bank Claim

- Georgian Opposition Calls December 6 March Over Alleged Use of Chemicals at 2024 Protests

- Severe Smog Covers Oskemen