KNB And Antikor Merger: Orda.kz Examines the Evolution of Kazakhstan’s Security Service

Operational exercises \"Kalkan-2021\" at the Oimasha training ground in Mangystau Region. Photo: National Security Committee of the Republic of Kazakhstan.

Operational exercises \"Kalkan-2021\" at the Oimasha training ground in Mangystau Region. Photo: National Security Committee of the Republic of Kazakhstan.

After the collapse of the USSR, the KNB transitioned from a successor to the KGB into a body responsible for everything from border protection to fighting corruption.

It has survived presidential transitions, reforms, the arrests of its leaders, and its involvement in the most significant political crisis in modern Kazakh history — Qantar.

What could Antikor’s loss of independence lead to? Orda.kz gathered assessments from former officers and analysts.

Since January 2022, the KNB has been headed by Lieutenant General Yermek Sagimbayev. The chair has ten deputies, all of whom have been newly appointed over the past couple of years. The first deputy is Ali Altynbayev. Economic security is overseen by Askhat Tuleuov, foreign intelligence by Major General Marat Zhumabayev, elite special forces unit "A" by Berik Kunanbayev, and the Border Service by Yerlan Aldazhumanov. The newly created anti-corruption service has been headed by Nurzhan Kussainov since July 8, 2025. The remaining deputy chairs — Bakytbek Rakhymberdiyev, Ruslan Sarkulov, Almas Naimantayev, and Kanatay Dalmatov — are assigned to territorial and operational sectors.

One of the first people we spoke with about the KNB’s evolution was former committee head Alnur Mussayev.

According to him, understanding the current situation requires going back to the 1980s, when the KGB of the Kazakh SSR had only just begun forming an economic security unit.

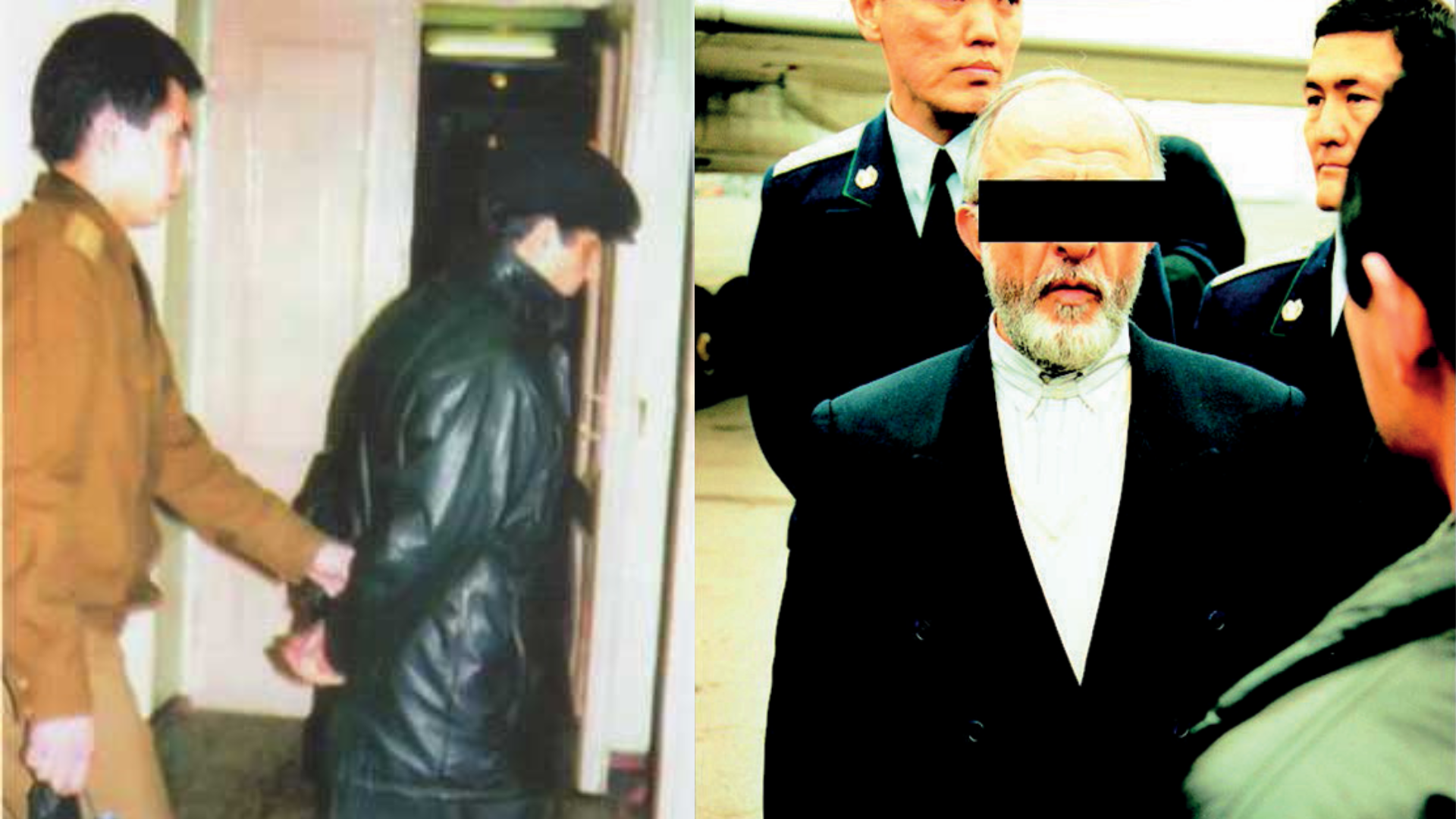

Alnur Mussayev: a former major general and former head of the National Security Committee. He led the agency during two periods (1997–1998, 1999–2001). He was close to Rakhat Aliyev, Nazarbayev’s son-in-law, and both were at the center of an internal political conflict in the early 2000s. As tensions escalated within the president’s inner circle, Mussayev emigrated to Austria. In 2008, he was detained at Astana’s request, but an Austrian court refused to extradite him, deeming the charges politically motivated. He was later convicted in absentia in Kazakhstan for treason and conspiracy. Alongside Aliyev, he became a symbol of the “elite split” — an attempt by elements of the security apparatus to push political reprisals outside the boundaries of the legal system.

At the time, the KGB infiltrated various structures, departments, and sectors of the economy. There was a power struggle between KGB military counterintelligence and the Ministry of Defense’s GRU. Economic security became entangled in nearly every field. Officers from the active reserve were stationed in major enterprises, taking control over ideological authority in party committees, Mussayev recalls.

Jeltoqsan

The turning point came in December 1986: following the brutal suppression of protests, Moscow tightened its grip on Kazakhstan, including over personnel policy in the Kazakh SSR’s KGB. Enterprise leaders began prioritizing “safe” decisions that wouldn’t raise suspicion over actual efficiency.

As a result, real threats slipped under the radar while reports falsely claimed everything was in order.

'Young people took to the streets in protest and were violently crushed by what were essentially international troops on permanent deployment. These were criminal actions against the Kazakh youth. Toward the 1990s, Ukrainians, Belarusians, and Russians were being placed in the leadership of the Kazakh KGB. Miroshnik arrived in Kazakhstan along with Kolbin. Later, the reverse happened: the Slavs departed, and the national cadres were brought in,' he recalls. 'A symbolic shift occurred in 1991, when Nazarbayev removed Miroshnik and appointed Vdovin — a ‘Kazakh Russian’ — as chair of the Kazakh SSR KGB. That marked the beginning of Kazakhstan’s state security history.'

The 90s

The KGB was later transformed into the National Security Committee. Legal frameworks were established, and reforms were mapped out. But in reality, the agency faced poverty and breakdown of labor. Even the head and deputy head of the economic security department, both holding the rank of colonel, had to "hustle" to get by.

I had to moonlight with my personal car to support my family, who lived like everyone else. Although before that I had great opportunities — I earned a fortune in foreign currency during a business trip to the Middle East. But by 1992, the money was gone — we’d bought a car, an apartment, and so on.

What does that say about the situation if even high-ranking officers, once flush with foreign earnings, found themselves back at the stove a few years later, wondering what to eat with their pasta—if they had any pasta at all?

Some turned to “economic connections,” others to moral flexibility. In this murky space between need and authority, some learned to navigate especially well.

At the time, Nazarbayev did everything he could to keep the National Security Committee from falling apart. Despite the devaluation, they tried to maintain salaries, but of course, the money wasn’t enough. Inflation was brutal.

Barlau

In the absence of financial motivation, another crisis emerged — ideological. Even agent recruitment hit a wall:

All the old missions — agent work, foreign intelligence, fighting anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda — continued, and we had to pivot. Everything became about monitoring the internal political situation. The KGB could recruit agents on a patriotic basis — ‘for Soviet power, for communism.’ But what sort of patriotic basis can you offer for building an independent Kazakhstan? You can’t say ‘for capitalism and business,’ Mussayev explains.

There were attempts to develop an alternative to the traditional value system from within. Mussayev says he personally pushed for a focus on national identity:

I had long debates about this with Bulat Baekenov (head of the KNB in 1992–1993): that once we had independence, a certain sovereignty — even if it was still limited by Russia— it was important to develop a patriotic direction rooted in nationalism. Nationalism as a positive ideological direction: independence, international language, and so on. But this idea was poorly developed. Most people in Kazakhstan at the time were Russian-speaking, especially in the early ‘90s. So it didn’t take hold.

According to Mussayev, the consequences of that ideological vacuum are still felt today.

"The KNB should have focused on intelligence and operational work, protecting the state from internal threats by Kazakh people. But in those conditions, Russia had the operational advantage — not just in Europe or the U.S., but also in the post-Soviet space and Kazakhstan too. The FSB and its counterparts were simply stronger.”

At the same time, the KNB took on a paradoxical role: it became both the main guarantor of state security and a potential threat to the government itself.

Neither the Ministry of Defense nor the Ministry of Internal Affairs — or any other Kazakh security agency — interfered in politics. Except for the KNB. Domestic political processes, events within the country, complex issues—all of that is directly the KNB’s responsibility. And because that’s so closely tied to the state, the KNB is, to some extent, a threat.

In such a system, says the former chair, personal loyalty becomes critical — hence the frequent rotation of leadership:

Because if Mussayev, or Mr. Shabdarbayev (who led the KNB in the mid-2000s) or someone else, stays in place too long, a problem could arise. Both I and Massimov (former KNB chief, convicted in the Qantar case) were charged with attempted coups. Dutbayev (who headed the service in the early 2000s) was tried for other offenses. All this shows that this structure of authoritarian power needs to be monitored very closely.

He acknowledges that the episode involving himself and Rakhat Aliyev was the precedent that made the authorities realize the KNB could begin operating independently.

In September 1999, Aliyev became head of the KNB’s Almaty and Almaty Region departments. In 2001 — already Nazarbayev’s son-in-law — he was appointed first deputy chair. His rise to the top seemed inevitable:

The country’s leadership has always feared the KNB. That’s been the case historically, perhaps in part because of my own influence — or Rakhat Aliyev’s. He was a public figure. Many said he wanted to become President. We created a real threat to Nazarbayev, and later to all those infected, says Mussayev.

In his view, this fear is reflected in the constant shifting of priorities:

There’s a continual change in functions. Intelligence is added to the KNB’s responsibilities, then taken away. Corruption cases are handed to it, then removed again. In essence, this is a direct and real state of security.

Mussayev warns that strategic objectives must not get lost amid routine tasks.

The KNB should be tackling corruption, but on an entirely different scale. Internationally, like the Swiss case, Kazakhgate, or Operation Sapphire. I believe that the KNB should study the following most important issues: intelligence, counterintelligence, and handling domestic political threats — terrorism, collaborationism, separatism. The rest should fall to other institutions: the Anti-Corruption Agency, the Interior Ministry, and the Prosecutor’s Office.

A Center of Power, Not of Solutions

Viewing the modern KNB purely as a relic of the Soviet system, however, risks overlooking a broader evolution.

Political scientist Gaziz Abishev urges taking a wider historical lens.

Abishev is a Political analyst. Graduate of the Pavlodar Pedagogical Institute and Queen Mary University of London (economics). Studied political science at the Gumilyov Eurasian National University. Former analyst at the Central Communications Service under the President of Kazakhstan and adviser to the Vice Minister of Investment and Development.

Of course, I’m not a historian of intelligence services,” he quips. “But if you look at the development of stable states, you’ll find they all needed a universal institution to uphold statehood — specialists in everything from the Russian Empire’s secret chancery to imperial advisers in dynastic China.

This kind of all-encompassing, somewhat shadowy institution, he argues, often serves a very practical function.

In the U.S., for example, the intelligence community includes more than 20 agencies. Yet the FBI handles counterintelligence, terrorism, white-collar crimes, and corruption — all at once. Its functions overlap with those of the CIA, DIA, NSA, and Homeland Security. That’s why they have a Director of National Intelligence who oversees the intelligence side across departments, and a Prosecutor General for the legal end.

In Kazakhstan, he says, the analog to such central coordination is the Security Council. From Abishev’s perspective, merging the KNB and Antikor is more about vertical alignment than functional consolidation:

Even if intelligence, counterintelligence, and other tasks were divided among separate agencies, the information would still funnel to the Security Council and end up on the President’s desk. So they always remain discreet — in one pocket of the state’s coat, so to speak. Whether they 'lie' in separate pockets or not — I don’t think that really matters.

As for the KNB’s role during the January 2022 events, Abishev cautions against jumping to conclusions:

This wasn’t a ‘special service conspiracy’ like Gaddafi leading a clique of officers. Most security agencies remained loyal to the constitutional order. The state prosecution only named specific individuals from the KNB — Karim Massimov and his associates. So I don’t believe it was a systemic or institutional coup attempt. Most KNB officers are loyal professionals, trained to serve as such.

He views the concentration of functions within the KNB not as a power grab but as a bureaucratic drift:

“Within the KNB, different departments operate with a high level of autonomy. Global intelligence agencies are essentially built on professional paranoia — they rarely intersect. Each service acts independently, even when under a single leadership structure.”

And the logic here is pragmatic:

This is probably being done because the President believes it's easier to manage through a single leader — less competition, fewer financial games between the heads of different services. What we’re seeing now isn’t the first time. Each individual service continues operating the same way it always has. says Abishev.

Honor? Valor? Fatherland

Sometimes, criticism sounds less like condemnation and more like a sober, if bitter, verdict — especially when it comes from someone who once served the system with loyalty, only to watch ideals drift away over time. When a security service loses trust by meddling in business or remaining silent at key moments, those who speak out often do so not out of spite, but from hard-earned insight.

That’s the case with military expert Daulet Zhumabekov.

Daulet Zhumabekov: A graduate of the Riga Higher Military Aviation Engineering School, he served in the General Staff of Kazakhstan’s Air Defense Forces. Retired in 2007 and later earned a law degree. Now active in human rights advocacy, working to expand protections for dismissed officers.

This kind of shift scatters the focus of KNB officers, distracting them from more pressing and immediate threats to national security. Moreover, we’ve already had experience with KNB officers investigating corruption crimes — and it didn’t end well: there were instances where criminal cases were opened against businessmen under fabricated charges, followed by extortion by committee leadership.

Behind the expansion of responsibility lies the failure of alternative institutions:

Unfortunately, in our country, it’s become a tradition: the agencies tasked with fighting corruption end up leading it. This was the case with investigators from the Ministry of Internal Affairs and the National Security Committee, who were themselves involved in corruption, and later with officials from the Financial Police.

He speaks from experience:

When the government sees that a system is completely rotten, it simply hands the responsibility off elsewhere. I personally filed complaints and dealt with both the Financial Police and Anti-Corruption Agency. Even with all the evidence in hand, I couldn't hold anyone accountable.

Zhumabekov believes that merging agencies shifts the political balance:

This definitely increases the influence of the National Security Committee and its leadership. They have an additional lever of pressure on those who do not agree with them, including those in high positions.

He also views the January 2022 events (Qantar) as exposing KNB vulnerabilities:

Qantar cannot be seen as a sign of the KNB’s ‘strength’ or ‘power.’ After all, if the ‘strong’ KNB had supported the president, Qantar wouldn’t have happened. And if the ‘strong and powerful’ KNB had actually attempted a coup, it most likely would have succeeded.”

Ultimately, he says, power hinges on trust, with a caveat:

Granting expanded powers always signals trust. It’s likely that after the reshuffling since January 2022, the President believes another Qantar is now impossible. But when it comes to fighting corruption, I wouldn’t count on the KNB succeeding just because the responsibility was reassigned. I fear a repeat of past patterns, and we’ll soon see some KNB officers rapidly growing rich.

Scale Dictates Form

Political scientist Farhad Kassenov believes that complex, multifaceted processes can't be reduced to simple evaluations.

Farhad Kassenov is a political scientist and media expert. He studied at Al-Farabi KazNU, majoring in Philosophy and Political Science, and continued his postgraduate work there. He holds a master’s in international relations from KazUIR & W and a PhD from the Institute of Philosophy, Political Science, and Religious Studies. He heads the research center A+Analytics.

Yes, there is expert opinion that the KNB is turning into a cumbersome structure, overseeing everything from foreign intelligence to border security. But at the same time, it’s important to consider the demographic factor: we are not a large country — just 20 million people. Creating separate specialized agencies may prove ineffective — sometimes it’s simpler and more practical to concentrate analytical functions within a single institution.

Transitioning to a different administrative culture is like swapping out the frame while leaving the same inner workings. And what happens if those inner mechanisms are run by professionals shaped by the old system?

Even today, figuratively speaking, some officers still salute portraits of Dzerzhinsky rather than Alikhan Bokeikhan. We face the classic challenge of building new institutions with people who are products of the old ones. This was the case in Germany after the WWII, and it is the case with us. Belarus, for example, kept the KGB name and its logic. I hope Kazakhstan follows a different path.

There are also process issues that hinder operations:

All of this happens behind closed doors. We only see what leaks out into the public space. It seems there’s a constant process of internal adjustment within the department — small, but ongoing changes. They may not be visible, but they’re there.

Even with the right structure, execution depends on content:

"Comparisons with the FBI or France’s DGSI aren’t entirely accurate. These are countries on a different scale — they have more resources and a larger pool of qualified personnel.

A better comparison might be with the Scandinavian countries, where security services also handle a wide range of tasks within a single agency. This doesn’t weaken their analytics or intelligence capabilities.

The real issue isn’t structure — it’s personnel. It’s about recruitment, compensation, and how professional growth is treated. If we were bringing in the best graduates, creating career pathways, and properly evaluating analysts' work, the outcome would be very different.

But we’re not seeing that yet. The private sector offers analysts more, and that’s causing a brain drain."

Kassenov ties the future of the KNB to international best practices:

We need a comprehensive national security concept — not in the Soviet mold, but drawing on Western and Turkish models. It is important to expand cooperation in the security sphere with the U.S., China, Türkiye, and France. This is normal practice, and it’s the path to a modern, transparent and professional KNB.

Even within the system’s center of gravity, there are no true levers:

If we’re talking about meaning in the security sphere, yes, the KNB is a key player. It provides analysis, scenarios, and threat assessments. The KNB provides recommendations. But the decision-making center is still the Presidential Administration.

The real issue lies elsewhere:

"There’s a lack of coordination between professional expertise and civil administration. That’s a systemic flaw — not just in Kazakhstan."

Kassenov urges caution in interpreting the KNB’s role in the January events:

We don’t know what happened internally — it’s all classified. It's impossible to evaluate objectively. Some call it failure, others sabotage. But the key concept should be accountability. [...] Accountability and independent oversight is the foundation of a strategy for ensuring such a scale.

He points to global examples:

In the U.S., for example, there’s a Senate committee that oversees intelligence agencies. It receives reports, budgets, and program details. We have something similar, but it still needs to be properly developed. If that system functioned effectively, perhaps we could have avoided a situation where the head of the national security service became one of the key figures in the events.

Original Author: Kamila Yermakhanova

Latest news

- Tokayev Congratulates Saudi Leaders on Founding Day

- Undocumented Kazakhstanis in South Korea Can Leave Without Penalties Until Late February 2026

- Kalkaman Metro Station Construction Continues in Almaty

- Kazakh Peacekeepers on the Golan Heights Receive UN Medals

- Only Names Left: More Than 80 Villages Disappeared in Kazakhstan in a Year

- Environmental Safety to Be Added as Constitutional Principle

- Russian Fighter Jet Makes Emergency Landing in Atyrau

- Kazakhstan’s Banks See First Early-Year Profit Drop Since the Pandemic

- Cyclone to Bring Snow, Rain, and Blizzards to Kazakhstan

- Investments, Aviation and Healthcare: Tokayev Holds Series of Meetings With U.S. Company Chiefs in Washington

- Kazakhstan Ready to Send Military to Gaza — Results of the «Board of Peace»

- Ex-Prince Who Sold a Mansion to Kulibayev Arrested in Epstein Case

- Almaty Will Not Build New Sports Facilities for the 2029 Asian Games

- Earthquake Recorded in Kazakhstan in 2020 May Have Been China’s Nuclear Test

- Kazakhstan May Move Constitution Day to March 15

- Kazakhstan’s Cinema Market: Kazakhfilm Fined, Kinopark Under Antitrust Scrutiny

- Kazakhstan Extradites Tax Fraud Suspect from Kyrgyzstan

- New 5.3-km Hiking Trail to Big Almaty Lake Planned for 2026

- Kazakhstan Introduces New Rules for Parcels Ordered from Foreign Marketplaces

- FlyArystan Appoints Executive from European Airline as CEO