‘I Don’t Remember What I Signed’: Former Bek Air Head Testifies in Court Over 2019 Plane Crash

Photo: Orda.kz

Photo: Orda.kz

Orda.kz looked into why the former head of Bek Air continues to deny responsibility, who he blames for the tragedy, and how he explains the photo of the Fokker’s iced-over wings.

The latest hearing on the crash of the Bek Air plane on December 27, 2019, turned heated. Summoned as a witness with the right to defense, Nurlan Zhumasultanov flatly refused to acknowledge being head of the airline—despite having said otherwise during the investigation.

At one point, a representative of the victims’ families accused two of her colleagues of “pushing” for Zhumasultanov instead of standing united with the prosecution.

Zhumasultanov’s behavior is not hard to understand. The trial is uncovering violations in Bek Air’s operations —layer upon layer of them — that may have led to the disaster that claimed 12 lives. This means someone in the company’s leadership will likely be held accountable. So far, the blame has been placed on the deceased captain, Marat Muratbayev, and co-pilot, Mirzhan Muldakulov.

As for the accusations of “double play” within the victims’ legal team, Judge Dastan Almagambetov did not comment. Yet one of the plaintiffs, Zhanetta Kameleva, pointed to case files showing that in 2020 Zhumasultanov had entrusted lawyers Nurlan Khalikov and Sergey Derzhavets with his defense during the investigation. Today, however, those same lawyers represent the victims, which Kameleva called highly suspicious.

The lawyers hit back, calling the allegation baseless. They were even supported by their opposing colleague, representing the families of the deceased pilots. Attorney Beibit Kendirbayev went further, saying Kameleva should be held accountable for slander. The judge again stayed silent, keeping alive the intrigue that has drawn journalists’ attention to the trial’s twists and details.

Are Airport Technicians to Blame?

The high-profile case is being heard in Almaty’s Turksib District Court under Part 3 of Article 344 of the Criminal Code: “Violation of traffic safety rules or aircraft operation, resulting in the death of two or more persons through negligence.”

According to prosecutors, pilots Muratbayev and Muldakulov should have ordered airport technicians to clear ice from both the tail and wings, but only the tail stabilizer was treated. As a result, the plane could not gain altitude, veered off the runway, and crashed into a house under construction.

Twelve people were killed and 69 were injured.

Prosecutors argue that the incomplete de-icing was the result of Bek Air management’s instructions to save money. Captain Muratbayev’s delayed reaction also played a role: before the flight, he had taken medication to lower his blood pressure, which prosecutors say impaired his performance at the most critical moment.

Prosecutors Aidos Palmanov and Baurzhan Seitov are presenting the charges. Defense attorney Beibit Kendirbayev, representing the deceased pilots, insists his clients are not to blame, arguing they carried out proper pre-flight checks and followed aviation regulations.

Representing the families of passengers are lawyers Nurlan Khalikov and Sergey Derzhavets. Unexpectedly, both lawyers have sided with their colleague on the defense team on many issues, often criticizing the state prosecution. They even sit together on the same courtroom bench.

Experts also testified, explaining how pilots should be retrained to fly new aircraft types and how airport technicians are supposed to prepare planes for takeoff. They then described how these procedures were actually carried out at Bek Air and Almaty airport.

The court questioned witness Nurlan Zhumasultanov, considered the former head of Bek Air. Called to testify, he immediately offered to clarify sections of the government commission’s report on the crash. Zhumasultanov argued the report was written in highly technical aviation language that many participants could not understand, and said he could explain its complex terms.

The judge, however, cut him off:

No need, we understand everything. This is already the tenth session where we’re reviewing the commission’s report. You’re not the only one with higher education — we have it too, said Judge Almagambetov.

Cross-examination of the witness then began. Lawyers for the victims spoke first, asking why Captain Muratbayev had ordered de-icing only of the plane’s tail.

The crew checked the wings and were satisfied with their condition. But they couldn’t inspect the stabilizer — it sits high up, about nine meters off the ground. So, to be safe, they ordered de-icing only for the stabilizer. Frankly, if I were in their place, I wouldn’t have touched it either: if there’s no buildup on one part of the plane, there won’t be any on the other, Zhumasultanov replied.

When asked about a psychologist’s finding that Bek Air pilots had a financial motive regarding the anti-icing, Zhumasultanov dismissed the claim.

That’s both prohibited and illogical. In fact, 153 liters of anti-icing fluid were sprayed on the Fokker instead of the required 40–45 liters — nearly four times more. Ticket prices cover all expenses, including anti-icing.

According to the witness, the tragedy was caused by the negligence of airport technicians, who mixed up the fluids: instead of using concentrated Type 1, meant to remove ice from the aircraft’s surface, they applied the weaker Type 4, designed only to prevent ice from forming.

According to the order issued by the airport to the airline, the liquid used was not the one requested by the captain. He had asked for Type 1, which comes from the factory as a concentrate, must be diluted with water at a 70/30 ratio, and heated for effectiveness. Instead, Type 4 was applied — a ready-made fluid that requires neither dilution nor heating, Zhumasultanov said.

He added that the technicians not only mixed up the fluid but also applied it incorrectly to the tail stabilizer.

The stabilizer was treated without regard to wind conditions. A service vehicle approached from the left, between the engine and tail unit, and sprayed the stabilizer — first on the right side, then the left. With winds of one to two meters per second, the spray drifted toward the right wing. It’s quite possible the crew, sitting inside the aircraft, could not see how the treatment was carried out. Had the fluid requested by the captain been used, it would have remained effective for 45 minutes, and no issues would have arisen. Its freezing point was minus 35 degrees, while the temperature at the time was only minus 10 to minus 12.

Throughout his testimony, Zhumasultanov explained in detail how anti-icing fluids should be prepared, applied, and recorded for airline–airport billing — turning the session into a crash course in applied chemistry and higher math.

Still, he acknowledged that ultimate responsibility lay with Captain Muratbayev, who was in charge of the aircraft’s pre-flight checks. The failure of the Fokker 100’s icing sensor, located on the nose underside, also played a role: it did not activate, leaving the crew unaware of ice on the wings. Zhumasultanov said he did not know why the sensor failed.

The victims’ representatives then recalled passenger photographs taken just before takeoff. Through cabin windows, several passengers had captured images showing frost on the wings. Prosecutors argue these pictures prove the aircraft was iced.

The lawyers then asked Zhumasultanov, as an aviation expert, to explain in simple terms how the windows were constructed. To illustrate his answer, he used a model of the aircraft.

The outer layer of the window is made of acrylic glass, up to 15 millimeters thick, and firmly fixed to the aircraft. Inside, the glass layer is softer, and at the bottom there’s a small hole about three millimeters in diameter. When the plane takes off, the pressure outside drops and the cabin is pressurized. Outside, the temperature can reach minus 60, while inside it stays around plus 20. To prevent passengers’ hands from freezing if they touch the window, the inner layer is made of plexiglass. During a two- or three-hour flight, passengers breathe in the cabin, and the moist air seeps through this tiny hole. It settles as frost inside the glass, not on the outside.

he said.

The lawyers pointed out that the photos were taken before takeoff.

Zhumasultanov suggested instead that the frost may have formed on the inner side of the double-glazed window during a previous flight.

The lawyers also asked Zhumasultanov how Bek Air monitored the quality of medical care for its pilots. According to the prosecution, flight crew members often concealed illnesses from management out of fear they would be grounded. Each missed flight meant lost income and fewer total flight hours, so pilots allegedly chose to seek treatment in secret.

Zhumasultanov dismissed these claims.

Airlines sign contracts with private medical centers operating under Kazaeronavigatsia. Pilots receive outpatient treatment there and undergo flight medical examinations. If doctors ground them for health reasons, the airline is immediately notified. Pilots aren’t reckless or suicidal. They go through medical commissions every six months, and they see psychologists, he argued.

He reminded the court that until January 1, 2014, airlines themselves could issue flight certificates, but since then this authority has belonged to the Civil Aviation Committee (CAC). If an airline continued the old practice of certifying pilots, it faced fines.

When asked whether Bek Air management had ever issued certificates without CAC approval, Zhumasultanov was categorical:

No, never. For example, if you have a category B driver’s license, can you drive a truck? No, only with category C you can.

The injured party’s lawyers then pressed him on why, as a member of the government commission investigating the December crash, he never proposed a critical experiment. They suggested that instead of relying solely on computer modeling, investigators could have rolled an empty Fokker onto the runway with instructor pilots to see in real conditions how competently the crew had acted during takeoff.

Zhumasultanov replied that the commission had asked the Ministry of Internal Affairs for permission to conduct such an experiment but was refused.

When prosecutors took over questioning, they asked how the airline managed crew operations in winter, particularly ordering services to clear aircraft of snow, dirt, and ice.

Zhumasultanov hesitated — and at that moment the tone of the trial shifted. Surprisingly, lawyers Khalikov and Derzhavets, representing victims’ families, objected to the question, saying such matters should be addressed to the airline’s official representative.

The judge sharply reprimanded them for interrupting the prosecutor. He then turned to Zhumasultanov directly: “Who created Bek Air? You?” The witness replied that he had merely “helped create” the airline.

But Judge Almagambetov reminded him of his earlier testimony.

You said: ‘I created the company in 2011. It was under my control. From April 2011 to May 2016, I was chair of the board of directors. I left in 2016 when I moved to civil service.’ Why are you now denying that you headed the airline?

Zhumasultanov attempted to distinguish between entities: the judge was referring to Bek Air Airlines JSC, founded in 2015, while he had been involved only at the beginning with an LLP that was later transferred to others.

The court then asked whether his family members were connected to the airline. The witness gave a somewhat muddled response: his wife, he said, had once worked for a ticket sales company, and his son had briefly served on JSC’s board of directors.

As for himself, he insisted, he had never been a founder of Bek Air. Trying to defend his position, Zhumasultanov could not resist adding a pointed remark to the judge.

Are we considering a plane crash here or what? What does the airline’s structure have to do with this case?

The judge replied coldly that it was directly relevant.

You are an interested party because you are the founder of this company. The case file includes a document from May 18, 2015, showing that the sole founder, Zhumasultanov Nurlan Tleubayevich, decided to sell 13% of shares to Dutch citizen Lindon Ruben. That document bears your signature. Members of the board have also testified that you are the founder.

Zhumasultanov stuck to his denial, saying he could not recall what he had signed during the investigation.

I was in shock at the time. I don’t remember what I signed!

Prosecutors countered by asking why, if he wasn’t head of the airline, he repeatedly appeared in the media in that role.

How else would he know about management’s plans? Zhumasultanov’s answer was blunt:

If a journalist wrote something, I’m not responsible for it. I was the representative of the aircraft owner, and that gave me the right to influence the airline’s policy.

Participants in the hearing noted that Nurlan Zhumasultanov had come well-prepared for his testimony. He arrived with a laptop and a mini-slide, announcing at the start that he was ready to display diagrams, maps, calculations, formulas, and other documents on the screen to back up his statements.

One lawyer cautiously asked how he knew so much about Bek Air’s internal affairs, and whether he had a personal stake in the airline’s success.

Zhumasultanov dodged the first question but answered the second with disarming brevity:

The airline operated successfully, it made all payments on time. If you are asking whether I had an interest, then yes, I did. I received my salary abroad — well, I did before the disaster… Yesterday, the commission members spoke in court, I talked to them, so I prepared for today’s hearing.

Editorial note

What strikes us is the categorical way Zhumasultanov now distances himself from Bek Air Airlines JSC, despite having had no objection five years ago when journalists openly referred to him as the company’s head.

We have not reviewed the protocol in which he reportedly confirmed his position. But a quick search brings up a CCS briefing dated December 28, 2019, where Vice Minister of Industry and Infrastructure Development Berik Kamaliyev stated that Zhumasultanov was the sole founder of Bek Air.

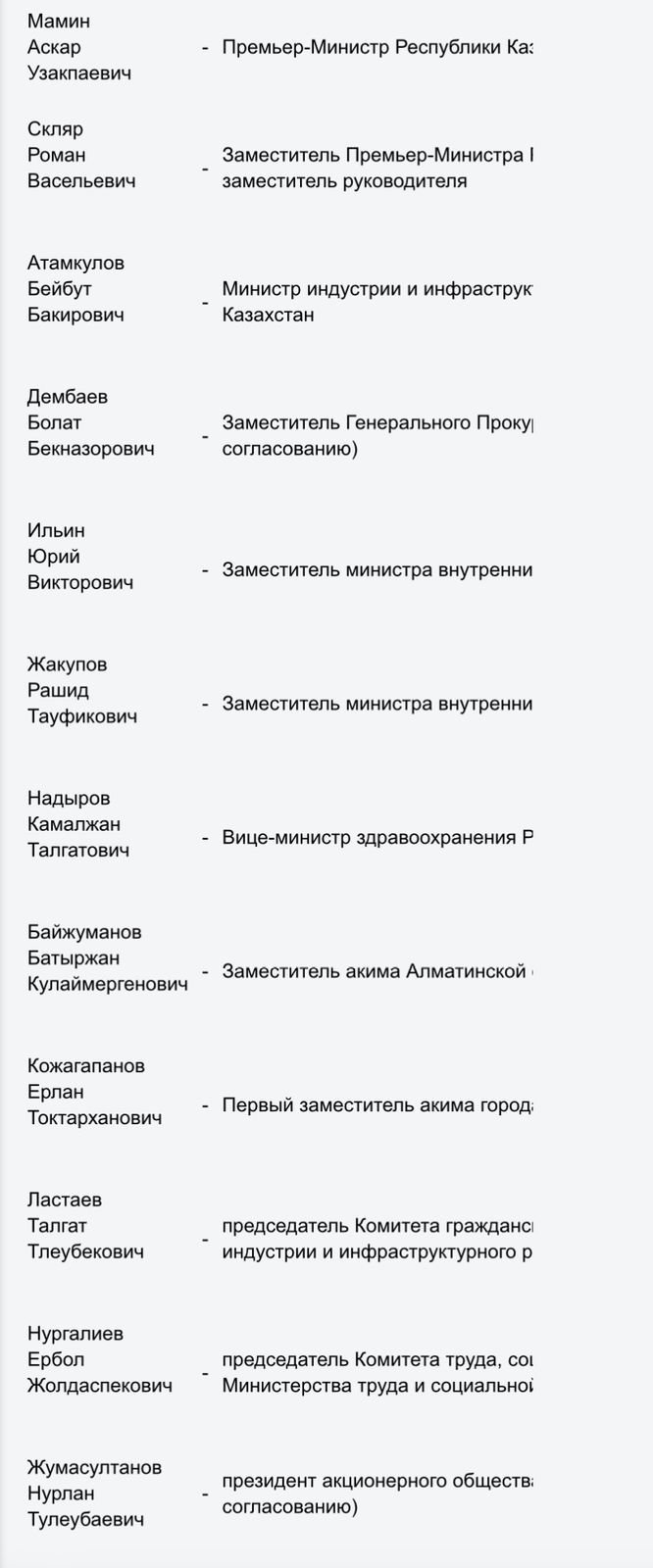

We also found a copy of Government Resolution No. 986, “On the formation of a government commission to investigate the causes of the Bek Air plane crash.” The annex lists the commission’s members, headed by Prime Minister Askar Mamin.

At the bottom of the list: Nurlan Tuleubayevich Zhumasultanov, President of JSC Bek Air Airlines.

Original Author: Zhanar Kusanova

Latest news

- The War in Iran Opens a Window of Opportunity for Kazakhstan’s Oil Sector, Analysts Say

- Iran Conflict Escalates Beyond the Gulf: What Kazakh Experts Say About Risks for Central Asia and Kazakhstan

- Kazakhstan Prepares Possible Evacuation of Its Citizens From Iran

- LRT in Astana Is Reaching the Finish Line: The Launch Is Expected in the Coming Months

- Kazakhstan Ready to Help the UAE Amid Escalation in the Region

- Tokayev Discusses Middle East Escalation With Qatar’s Emir

- Airlines Ready to Bring Kazakhstanis Home From the Middle East

- Tokayev Sends Support Messages to Gulf Leaders Amid Regional Escalation

- Kazakhstan Bans Its Airlines From Flying Over Several Middle East Countries

- Astana Strengthens Security Measures Amid Escalation Around Iran

- Tokayev Meets U.S. Ambassador Stufft, Discusses Board of Peace Cooperation

- Mangystau Launches AI-Assisted School Monitoring to Prevent Teen Suicidal Behavior

- Kazakhstan to Supply UK With Critical Minerals

- AI Faculties for Educators to Open in Kazakhstan: What Other Changes Are Coming to the Education Sector

- There Are Medals — But Not Enough Ice: What’s Happening to Figure Skating in Kazakhstan

- Is Kazakhstan’s Nuclear Power Plant Project at Risk After New UK Sanctions? Rosatom Responds

- Prosecutor General’s Office Suspends Extradition of Navalny Ex-Staffer Detained in Almaty

- Former EBRD Executive Jürgen Rigterink Elected as New Independent Director on Bank RBK’s Board of Directors

- Kazakhstan Near Bottom of Retirement Comfort Ranking

- Kazakhstan to Open New International Flights Across Asia, the Middle East and Europe